Donor Stories

Harold Appleton: A Lifetime of Stewardship

For Sonoma Land Trust, environmental stewardship is a driving force of our organization and part of everything we do – from conserving land to finding nature-based solutions for climate resilience to fostering the next generation of stewards through our educational programming.

For long-time volunteer, contractor, donor, and Professional Forester Harold Appleton, environmental stewardship has been the driving force of his entire life.

Harold credits one childhood experience in particular as igniting a spark in him. Growing up on Long Island, Harold and his friends loved playing in a nearby wetlands they called “the swamp,” even ice skating on it in the wintertime. Then one day, developers arrived and began paving over and building houses on the kids’ beloved swamp. To make it worse, the houses turned out to be structurally unsound, since they were built on unstable wetlands.

“I learned at a young age,” Harold explains, “how development can rob us of our ‘natural playgrounds.”

After attending UC Santa Cruz’s Environmental Studies program, Harold completed forestry school at UC Berkeley and began working in the Calaveras Big Trees State Park in the late 1970s, under the direction of a UC Berkeley Forestry professor emeritus named Harold Biswell.

“I was fortunate as a young man to get to work with Dr. Biswell,” Harold remembers. “At a time when it was a relatively rare practice, he was an early proponent of prescribed burning.” Harold recalls that Dr. Biswell’s teachings were similar to the traditional Indigenous practice of using ‘good fire’ as a tool for forest health. But back then, when fire suppression was the rule, Dr. Biswell came under a lot of criticism from fire professionals, foresters, and even fellow scientists and researchers who treated his ideas as being out of alignment with theirs. “Some even called him ‘Harry the Torch!’”

Though he couldn’t have known it at the time, the lessons Harold learned about ‘good fire’ from his mentor would come full circle much later in his life, including in the work he does today with Sonoma Land Trust.

While continuing to work as a forester, Harold launched a native plant nursery that he ran for 18 years, first in Mendocino and then relocating to Sonoma County. In the late 1980s, he began volunteering with Sonoma Land Trust as a monitor for the Land Trust’s Little Black Mountain property, periodically checking for signs of erosion and property line encroachment.

In the late 1990s, David Katz, the Land Trust’s executive director at the time, asked Harold if he would develop a forest management plan for Little Black Mountain, and so began another layer of Harold’s stewardship commitment to the Land Trust, this time as a professional contractor.

Through Harold’s leadership, Sonoma Land Trust has implemented a multitude of projects over the years addressing forest and wildland fuel management, property infrastructure, erosion control, and trail development to ready our preserves for educational programs and recreational activities.

Then in 2017 came the catastrophic Nuns and Tubbs fires. Of course, Harold had seen many, many wildfires over his 40 years working in forestry, but nothing prepared him for the mega-fires that ripped through Sonoma County that year.

“We knew the forests were in a very dangerous state,” he recalls, referring to the high levels of fuel loads and years of drought. “But the severity of those fires surprised everyone – the fire behavior was like nothing we’d seen before.”

Yet in the aftermath of the disaster, Harold sees a silver lining in how landowners, CAL FIRE, the Land Trust, and its partners have all come together to implement prescribed burning and fuel management on a very serious level. In his four decades as a forester, employing ‘good fire’ as he’d done with his old mentor Dr. Biswell had never been an option. Harold remembers working on forest management plans with the Land Trust in the years leading up to 2017, wishing that prescribed burning could be a management practice.

“At the back of our minds, we wanted to do the prescribed burning, but there were just too many obstacles and legal considerations,” Harold says. “Now, legislation has been passed to do precisely that.”

Even as he eases into retirement, Harold plans to continue his involvement with Sonoma Land Trust. “The fact that the Land Trust takes land stewardship so seriously is huge – it’s what keeps me going with the organization. That and the people I’ve worked with here.” He calls out his relationships with former Director of Stewardship Bob Neale, and Melina Hammar and Shanti Edwards.

“Shanti has a way of keeping me engaged,” Harold explains, “always inviting me out to different projects, whether as a volunteer, a contractor, or just plain curiosity.”

One theory of environmental stewardship categorizes stewards into three roles: doers, donors, and practitioners. Harold Appleton is someone who embodies all three roles through his partnership with Sonoma Land Trust and in his lifelong dedication to stewardship.

Harold was interviewed by CAL FIRE’s Jason Clay October 9, 2023 during the first prescribed burn at Little Black Mountain – something he helped set the stage for 20 years ago. Watch this video to learn more about his thoughts on that historic day.

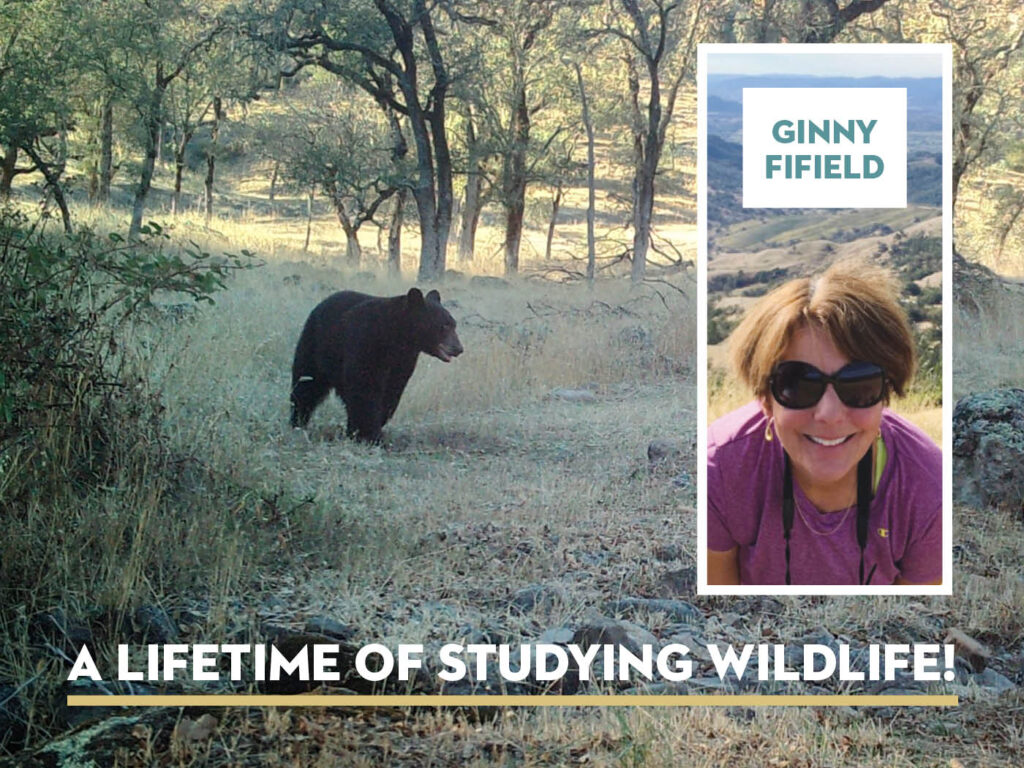

Member Spotlight: Ginny Fifield

Sonoma Land Trust volunteer and donor Ginny Fifield can often be found on our preserves strategically placing wildlife cameras in key locations to record videos of the deer, raccoons, foxes, coyotes, mountain lions, and even bears that live in Sonoma County!

Ginny’s fascination with wild animals began in childhood when she was lucky enough to have “behind the scenes” privileges at the Milwaukee County Zoo (the zoo director was a close family friend).

“I grew up in the zoo!” Ginny explains. “I played with baby African leopards and Siberian tigers and got to watch the staff bottle-feeding them. It was just normal to me.”

When she was older, she took a position in the zoo’s education lab for children, introducing them to boa constrictors, flying squirrels, and tarantulas.

In 1972, Ginny set off for Brown University in Rhode Island where she completed an Independent Concentration in Animal Behavior.

Over the course of her career, Ginny has conducted field research with black-footed penguins in South Africa, bats in Tennessee, coyotes in Marin County, and jaguars and puma in Belize.

When Ginny first came to California in 1994, she worked with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife in the Eastern Sierras on a telemetry study that involved capturing mountain lions in the wild, fitting them with radio collars, then releasing them and tracking their movements. The goal was to learn about the impacts of human encroachment by discovering things like where the animals lived and what they ate, to better understand how they could thrive in the future.

For many years, Ginny has worked extensively with nonprofits and government agencies in Marin and Sonoma County setting up and maintaining cameras to document wildlife presence and activity.

After moving from Marin to Sonoma County in 2013, Ginny began volunteering with All Hands Ecology’s (AHE) Living with Lions project, headed by wildlife ecologist Quinton Martins. A long-time partner of Sonoma Land Trust, ACR’s Bouverie Preserve neighbors the Glen Oaks Ranch property near Glen Ellen.

In 2018, Ginny set up the first wildlife cameras at SLT’s Bear Canyon Wildlands. A dedicated volunteer, she has continued her work with Sonoma Land Trust staff over the past five years to document wildlife on our preserves, including Laufenburg Ranch and Live Oaks Ranch.

When Black Bears first started appearing on wildlife cameras in Sonoma County, Ginny joined the North Bay Bear Collaborative, which grew to include Sonoma Land Trust and other nonprofits and government partners. The cameras Ginny placed on the properties provided documentation that Black Bears were crossing through our preserves.

A resident of Healdsburg, Ginny says, “I’m thrilled that there’s an organization like Sonoma Land Trust that recognizes the importance of preserving land for open space and wildlife corridors. The Land Trust is doing an excellent job of acquiring and maintaining these properties, while focusing on the scientific aspect.”

From playing with baby leopards and Siberian tigers at the zoo to studying jaguars in Belize to helping document wildlife corridors in Sonoma County, Ginny brings a lifetime of expertise to her work with Sonoma Land Trust. Thank you Ginny!

Oak Hill Farm

Oak Hill Farm’s Arden Bucklin-Sporer and Kate Bucklin are lighting the way for the next chapter of the family’s legacy.

Over a half century has passed since Anne and Otto Teller began their sustainable farming practices at Oak Hill Farm in Glen Ellen, and today it is as vibrant and resilient as ever. The Tellers were among the founding members of Sonoma Land Trust, and they donated a conservation easement over their 677-acre property. As one of Sonoma Land Trust’s first conservation easements, this thriving organic farm and additional 500-acres of wild, undeveloped land are now protected forever. Kate and Arden, Anne Teller’s daughters, have continued implementing sustainability practices on the farm and have integrated fire-adaptive practices, intentionally returning good fire to the land for the first time in over a century.

In 2017, the Nuns Fire burned through most of the property, including portions of the farm and various buildings as well as undeveloped forests and shrublands outside the farmed area. These fires were a wake-up call and delivered an urgent message to the family, and our entire county, that could not be ignored. The fires came at a time when Anne Teller, then in her late 80s and battling cancer, had submitted a grant application to fund the clearing of woodland understory for 93 acres.

“My mother knew that someday fire would be an issue but there were never the resources to prepare for it and it remained on the backburner,” said Kate Bucklin. “She was recognized a long time ago for having cleared roughly 2 acres by hand when no one was doing this kind of work and she set an example of what good land stewardship practices could look like. She also understood the value in grazing and was an early adopter of using goats to keep down the weeds.”

The grant Anne applied for was through a Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) program which offers financial assistance to farmers, ranchers, and landowners to manage or steward their lands, and provides personal assistance with the grant proposal process. For Arden and Kate, this was the exact support they needed to take the next step and to continue their mother’s devoted care of the property.

“At first NRCS seemed unapproachable, but they got on the phone and walked me through the whole thing,” Arden shared. “It seems to me that funding for this kind of work is left because landowners are often too busy and the process too complicated to navigate to complete the application. I appreciated that they were motivated to help us.”

The grant was awarded, and they brought in a crew to conduct the first phase of understory thinning. Hoping to expand their management options to include beneficial fire, Arden and Kate sprang into action, surveying and planning with Fire Forward, a program at All Hands Ecology, which also happens to be their neighbor. Guided by the team’s burn boss, Sasha Berleman, they assessed the property and broke it up into several regions, including the public-facing Red Barn section, and scheduled a burn over some 24 acres. Following a recent November rain, the prescribed fire crew started ignitions at the top of the hill and brought fire all the way down the hill without any issues.

“There are so many people doing this work now and a lot of resources out there for landowners who want to better protect their land from destructive wildfires,” said Arden.

Arden believes that “The goal is to have the healthiest forest you can have and build protection against the next fire.”

Fire was introduced around oak trees in areas with a thick layer of dead grass, or “thatch”, often referred to as “fuel” because it is dry and can easily take fire across the forest floor and into the tree canopy. By burning thatch, native plants have room to regenerate and offer protection to oaks by clearing the space around them.

“Since the thatch has been cleared, the native plants are coming back, allowing more variety of grasses and biodiversity,” said Kate. “I have noticed that the hawks are frequenting this area more — probably because the clearing improves the visibility of prey moving across the land.”

“We expect that in Spring we will discover seeds that have been dormant for 50 years have been brought to life by the fire’s heat. It is too early in the season to witness this transformation, but we know that this is another benefit fire brings to the land,” Arden added.

With the addition of the prescribed fire practices to manage, rebalance, and restore their grasslands and woodlands, they can also now turn their attention to the task of removing hundreds of acres of burnt trees left standing after the wildfires. In addition, they are exploring the benefits of animal grazing to keep the thatch and weeds in check until the next prescribed fire is scheduled.

“If multiple landowners in one area can work together, they can benefit from the resources and possibly apply for a larger landscape grant for this work,” Kate suggested.

Oak Hill Farm, Sonoma Land Trust’s Glen Oaks Ranch and Secret Pasture Preserve, and All Hands Ecology’s Bouverie Preserve form a protected core of more than 1,500 acres of connected open space in Sonoma Valley near Glen Ellen. For decades, we have worked on shared priorities across property lines, including watershed health and wildlife passage, and in recent years, have expanded our focus towards fire resiliency on a larger scale.

“There are a lot of great scientists in Sonoma County and a lot of people are active in this work. I am happy to be a resource for any landowner who needs some assistance with this process and encourage them to reach out to me for help,” Arden offered.

Sonoma Land Trust is a valued partner in this work and is one of the six organizations that make up the Sonoma Valley Wildlands Collaborative, working with CalFire on landscape-scale forest management and prescribed fire projects throughout Sonoma Valley.

Oak Hill Farm is protected through a conservation easement held by Sonoma Land Trust, ensuring it will remain conserved forever.

To learn more about Conservation Easements or our Living with Fire strategic plan, email us at info@sonomalandtrust.org

We are incredibly grateful to the entire Bucklin/Teller family and their spouses for their support over multiple generations, which continues to sustain the work we do across the county. We are lucky to have them as part of our Sonoma Land Trust community.

A Force for Nature Spotlight: Santa Rosa Southeast Greenway Founders Speak About Mission

For over a decade, the vision of transforming an abandoned strip of land into an urban greenway has been at the forefront of the Santa Rosa Southeast Greenway Campaign’s mission. Linda Proulx, Southeast Greenway Campaign founding member and Sonoma Land Trust Legacy League member, and Thea Hensel, co-chair of the Southeast Greenway Campaign and Sonoma Land Trust Evergreen member, explain the importance of this project and why it’s also important for them to individually support Sonoma Land Trust.

Linda emphasizes the alignment between the two organizations, stating, “Our vision of creating a vibrant urban greenway perfectly complements Sonoma Land Trust’s mission of providing equitable access to nature while conserving land for future generations.” She added, “The partnership between our organizations is one of the reasons why I personally support Sonoma Land Trust having seen the tremendous value they bring to this work.”

Linda’s sentiments are echoed by Thea Hensel, who emphasizes the unique qualities of the greenway. “The Southeast Greenway offers a diverse range of landscapes, from open spaces, shaded parks, creeks and streams to stunning hillside vistas,” she explains. “These attributes make it a valuable asset to the community, and we are grateful for the unwavering support and guidance provided by the Sonoma Land Trust and the vital role they’ve played in shepherding this project.”

At the heart of this collaboration is a commitment to connecting communities with nature. It also exemplifies what can be achieved when both organizations leverage their strengths and resources to transform ideas into reality, creating lasting benefits for both people and the planet. The outcome will not only benefit the local community but also contribute to our larger environmental conservation efforts and the 30×30 climate resilience goals.

As we move closer to realizing this vision together, we express our gratitude to all members of the Southeast Greenway Team and their supporters for their dedication and hard work and the many ways they support Sonoma Land Trust. Their tireless efforts have been instrumental in advancing this project and we value their partnership.

Learn more about the latest updates at https://southeastgreenway.org

From Conservation Council to Columbia: A Scholar’s Journey in Environmental Sciences

Bertha was always interested in nature. The youngest of three girls growing up in the Roseland section of Santa Rosa, she would imagine the sounds of cars rushing by her window on Highway 12 were those of crashing ocean waves. A trip to play in the park required public transportation, and this confined her to the little bit of nature right outside her door. She was drawn to the single, tall tree growing outside her window, and pulling a handful of bark off the tree, she did what any young, internet-savvy kid would do: she Googled it. A Redwood!! Bertha’s inclination toward “field research” emerged before she even grasped the concept, as she made discoveries and indulged her curiosity about the world around her.

During her freshman year of high school, Bertha came across an advertisement for an outdoor education program hosted by Sonoma Land Trust in her school’s monthly newsletter. Despite feeling somewhat apprehensive, she applied to the Conservation Council program. However, she wasn’t selected due to the program’s limited capacity. Two years into the Covid-19 pandemic, as the world began to reopen and Bertha entered her junior year, she decided to apply once more. This time, she succeeded! Bertha became part of a group of 20 students who dedicated over 140 hours both online and in the field, deepening their understanding of science within a living laboratory setting.

Bertha quietly settled into the programming as she tried to follow along with the Zoom workshops, learning how to catalog wildlife from field camera footage the group had set up the week before. Their focus was to monitor the wild turkey population at Laufenburg Ranch Preserve which they concluded to be the Rio Grande Wild Turkey and that there are no native wild turkey species left in California. Bertha shared, “I was surprised to learn that this species was not native and was introduced from a flock in Texas.” The team spent hours counting turkeys captured on camera, while also learning the process of cataloging each entry and subsequently comparing their data to previous years to identify changes or similarities.

“That winter, we had historic atmospheric river events, which meant we saw more plants and ticks for the turkeys to feed on. We also learned how to adapt when the field cameras filled with water from the rains and we lost data sets and had to rely on other methods to complete our research,” Bertha said.

The Conservation Council participated in weekly field trips at local preserves. They hiked the redwoods at Laufenburg Ranch, kayaked at Sears Point Ranch, and conducted field notes with watercolor paintings at Sonoma Mountain Vernal Pools Preserve. The first year was a hybrid program and Bertha shared that “the online workshops were challenging to stay focused; however, our field trips and outings kept me engaged. I enjoyed dissecting wildflowers to learn about them and crafted a bookmark with pressed petals where I named each section of the flower’s anatomy.”

In addition to the hands-on research and nature-based workshops, the program’s curriculum emphasizes essential life skills that Bertha’s high school has not provided. These practical skills include how to apply for college and what to consider when vetting the offers, financial responsibility including healthy spending habits and understanding student loans as well as an overview of the conservation science fields. All of this serves to deepen the students’ comprehension of the opportunities within science and conservation, impressing upon them the need for their skills and talents in the field.

“In my sophomore year, I knew I wanted a career in the environmental field but thought I only had two paths: Environmental Science or Environmental Law”. Now as a senior and near the completion of a second year in the program, Bertha builds upon her science and leadership skills as she co-leads her team’s research project focused on investigating the potential effects of vegetation species on soil chemical properties. Delving deep into the science and visiting the U.C. Davis Horwath Biogeochemistry and Nutrient Lab, has expanded her view of the paths available to her.

In addition to the hands-on learning and skills building, she shared “The career expo we attended as part of the program this year, provided me with the opportunity to learn about the many other opportunities that I had not been aware of. The Conservation Council opened up opportunities that I didn’t know were available to me.”

Inspired by this newfound path aligned with her skills and interests, Bertha began taking classes at the Santa Rosa Junior College to reinforce the skills she was acquiring at the Conservation Council. These included courses in climate science, statistics, and marine biology. Bertha’s schedule leaves little time for rest as she packs in high school coursework, weekly Conservation Council workshops and outings, Junior College classes, and participates in youth programs including ¡DALE!, Latino Service Providers, and Youth Commission on Human Rights. She meets her responsibilities and attendance all while relying on our local public busses and trains to get from campus to campus.

Bertha begins her college career already ahead of the curve, as she adds five associate degrees from the Junior College in Environmental Studies, Natural Sciences, Spanish, Humanities, and Latin American studies in addition to her high school diploma.

Graduation day in late May marks the beginning of a summer internship with the award-winning non-profit Point Blue Conservation Science, after which Bertha will pack her bags for the Big Apple – New York City. Bertha’s dedication to her studies has earned her a full-ride scholarship to the prestigious Columbia College, including housing. It is there that Bertha will begin the coursework to fulfill an Environmental Chemistry degree, which she hopes to apply to research studies that can address climate-driven catastrophes like coral bleaching.

From a quiet suburban upbringing to the bustling streets of New York City, Bertha’s journey epitomizes the power of passion, perseverance, and the transformative potential of education. Bertha truly is a Force for Nature!

A Force for Nature Spotlight: A conversation with supporter Maria Cardamone

When Maria was a teenager in Washington D.C., she spent her weekends backpacking in the Appalachians, and she vowed that one day she would live in the wilderness. “It took a while to realize that dream,” she says from the porch of her house between Bodega Bay and Jenner. Maria and her husband, Paul Matthews, live several miles inland, on 250 acres surrounded by state park lands adjacent to the Willow Creek watershed area.

It was here one evening in 2019 that Maria penned her goats in the barn for the night and left her two llamas out to graze like so many other nights before. When she saw their dead bodies the next day, Maria called Quinton Martins, asking if it was a big game kill.

A native of South Africa, Quinton grew up with large animals and has studied them his whole life. Now in Sonoma Valley, his company True Wild partners with All Hands Ecology, tracking the behavior and health of mountain lions through the Living with Lions program.

“After getting my call, he came out to the coast from the eastern part of the county to observe. He told us to dig up Rocky, one of the llamas we had just buried. It was one of the few times I ever heard my husband swear.” Quinton used the llama to create a live trap and left the property. At 3am the following morning he called with news from the webcam: “We’ve got a kitty,” he told her.

Quinton knew that mountain lions are loners. They feed primarily on deer and unsecured livestock and usually come back to the site to eat the rest of their prey. Maria watched as the research team returned to the property and sedated the cat whom they named P14 “Paul” in honor of her husband (although it actually stands for Puma). They took DNA samples, checked his teeth, and fitted him with a collar so they could track his behavior. Through P14, Quinton was now about to extend his research and education into the coastal area of the county.

“I just couldn’t kill the lion,” said Maria. “It was on me that the llamas died. I should have enclosed them.” In Maria’s mind, another life should not be sacrificed because of her lapse in judgment.

“The mountain lions live here too. Even though they are large and frightening and at the top of the food chain, they are also fragile and vulnerable. They die easily, from being shot or poisoned from eating chemicals sprayed on the plants. It is the owner’s responsibility to enclose and protect their livestock from predators. The mountain lions are merely getting food to survive.”

Deer are one of their main food sources, and the lions’ survival helps keep the deer population in check. Mountain lions’ lives are tough and they’re shy. They avoid humans.

“I got to touch him while he was sedated,” Maria tells me. “His fur was thick and stiff. His tail was the size of my arm and felt like one long piece of muscle. Very formidable. He lived for a few years before he was tragically shot by a rancher near Sea Ranch. It isn’t right.” Maria and Paul have made their property more wildlife-friendly by removing old fences.

Like the Sonoma Land Trust, Maria, and Paul partner with local organizations to further their ecological goals. “We work with the Russian River SHaRP program (Salmon Habitat Restoration Priorities) to repopulate salmon in the creek and with Sonoma County Regional Parks to provide access for hiking and camping.” As part of their plan to educate people and remediate the land, they have invited groups of women to do vision quests in the summer, making the land a safe and accessible environment. They’ve also brought other diverse groups out to experience the wilderness.

Maria and Paul’s connections with people, agencies, and the flora and fauna around them mirror the mission of Sonoma Land Trust, an intent to “protect the open, natural, and working lands and waters of Sonoma County to secure healthy and thriving futures for all.”

“We love the work of Sonoma Land Trust, especially their Greenway Project in Southeast Santa Rosa,” says Maria. “And we love it here, even though the 4-mile dirt road can be a real pain, especially when it floods. People protect what they love! We love the land. Allow people to have access to these areas, don’t beat them up with laws. Once they are out in nature, they will also work to protect it.”

Maria’s perspective shows a vast connectivity to our earth and all beings who live on it. It grows our connection to each other. It benefits us all.

Interview and article compliments of Sharon Bard

My Reasons Why

Every morning, rain or shine, I start off with a walk to clear my mind, set the tone for the day, and yes – make my Apple Watch proud of me. Luckily, I can easily find a quiet place to walk, a bit of open space to explore, and a place to connect with nature. That gives me a calming balance to handle whatever stresses lay ahead.

Growing up, I probably used a similar technique.

Fight with my big sister? Go climb a tree.

Exam-time overload? Head to the ocean.

Nature always had the answer to life’s problems.

Appreciation of, and respect for the environment was a big part of my science teaching career and I have seen firsthand both the excitement that nature can provide to students, as well as its calming effect. Despite the current all-engulfing attention to cell phones, I am convinced that 20 years from now, positive childhood memories will still zero in on times spent with friends and families outdoors.

Sonoma Land Trust is creating some of those memories: discovering what lives in the mud at Bay Camp, a family hike on one of our preserves, or a picnic in a new local park. Preserving Nature Nearby is a major focus of the Land Trust’s conservation efforts – ensuring equitable access to nature through parks and open space for everyone regardless of who you are or where you live. That is really important to me, as is the Conservation Council program, through which teens directly engage in conservation research and learn about potential career opportunities – taking action to make a difference.

That is what Sonoma Land Trust is all about – finding nature-based solutions to tackle the impacts of climate change and protect essential lands, waters, and threatened species. During the past few weeks, local headlines have featured major accomplishments of Sonoma Land Trust working with community partners: the acquisition of 174 acres of lush meadows and vernal pools; securing 750 acres of the Sonoma Developmental Center property as open space; the expanded protection of watersheds and wetlands as part of proposed solutions to the floods on Highway 37; and the Land Trust’s first large-scale urban project—Santa Rosa’s Southeast Greenway.

Sonoma Land Trust is investing in nature, the community, and our future. It feels great to support that investment.

-Judy Scotchmoor, board member, donor, and major cheerleader of Sonoma Land Trust

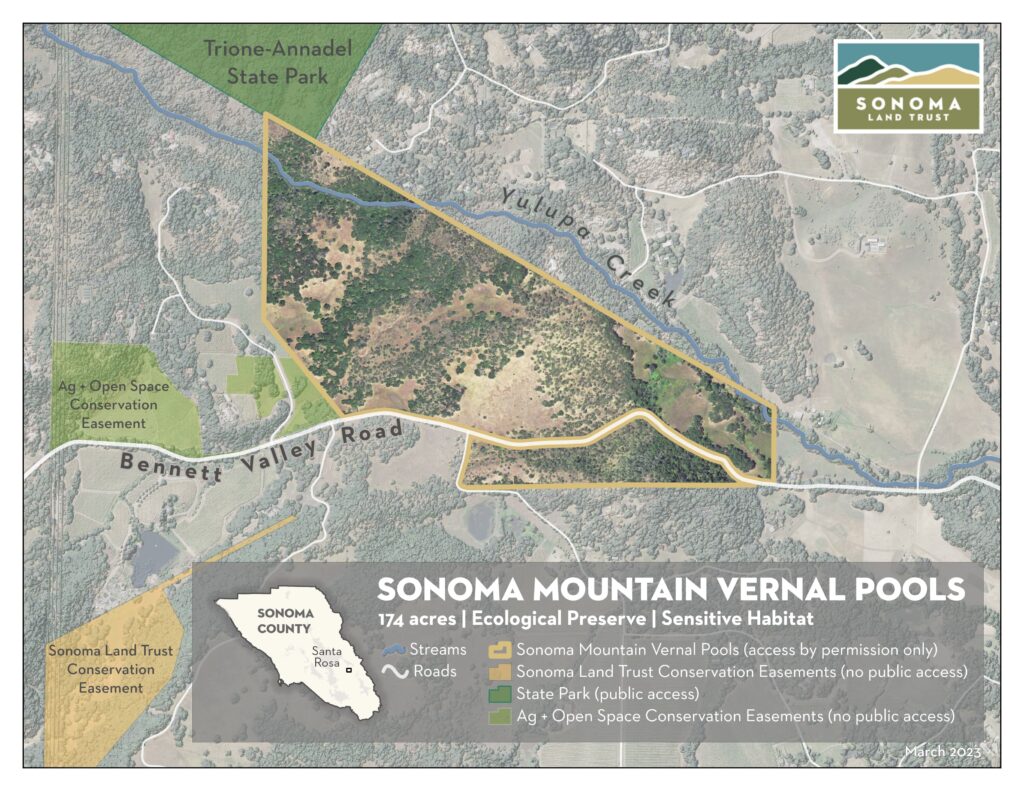

Sonoma Mountain Vernal Pools

Property Type

Ecological Preserve

Acreage

174

Protected in

2023

Region

Bennett Valley

Sensitive habitat / Access by Permission

Hábitat delicado / Acceso solamente con permiso

Streams, wetlands and vernal pools, surrounded by lush oak woodlands and sweeping vistas of the Sonoma Creek watershed along Bennett Valley Road between Santa Rosa and Glen Ellen.

Read the Press Release Here

Location

Glen Ellen, California.

Bennett Valley Road, Adjacent to Trione-Annadel State Park

Natural Features

Conserving the Sonoma Mountain Vernal Pools property protects rare and threatened plant species, seasonal vernal pools, and conserves a significant portion of an important wildlife corridor.

It also ensures the ongoing health of property’s natural features, including mature oak woodlands, intact grasslands, and portions of Yulupa Creek which feeds cold water to the Sonoma Creek, home of steelhead trout and chinook salmon.

Acquisition & Stewardship

Acquisition: Sonoma Land Trust in partnership with Sonoma County Ag + Open Space purchased the property on March 10, 2023. This purchase was also generously supported by funding from individual donors, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the State Coastal Conservancy, and the California Natural Resources Agency.

Stewardship: Sonoma Land Trust will own the property and manage it for several years as part of our ecological preserve portfolio with the goal of eventually transferring the property to a public agency.

30×30

This is Sonoma Land Trust’s first land purchase of 2023, and it conserves a healthy, ecologically sensitive habitat, while also contributing to California’s 30×30 goals, the state’s initiative to conserve 30% of its lands and waters by 2030. Currently in Sonoma County, approximately 22% of our lands have been conserved due to the work of land trusts, county and other government agencies, and conservation partners.

Click here to learn more about 30×30

To reach the goal of conserving 30% of the county by 2030, 78,000 more acres must be protected in the next seven years. Land trust acquisitions and conservation easements are a crucial part of reaching this goal and Sonoma Land Trust’s work towards conserving 30×30 is helping to combat the biodiversity and climate crises.

The opportunity to conserve this property is made possible in part by California’s 30×30 initiative. Sonoma Land Trust is a recipient of critical funding that makes purchases like this one achievable.

Vernal Pools Species: Click/Scan for the Calflora Species Guide for the Vernal Pools

Property Species List: Click/Scan for the Calflora Species Plant Guide

Download our species guide for more information about this property

History

In 1959 Benjamin Swig, a noted real estate developer and philanthropist, purchased land along Bennett Valley Road as a weekend and seasonal respite from his busy urban life, saying simply, “I wanted a place to rest.” Eventually, the property was transferred to two sisters, Benjamin’s granddaughters, Patricia Dinner and Carolyn Ferris, and over the past 60 years it has been the central gathering place for five generations and holds some of the family’s most cherished memories and gatherings. These celebrations are rooted in a tradition of honoring the bounty that the land provided, and it was this love for the land that motivated the family to conserve it forever through the transfer to Sonoma Land Trust.

Patricia Dinner, who raised her family on the property, spoke to this reverence for the land when she said, “It saddens me that we are seeing large pristine areas developed by urban sprawl leaving fewer natural, unspoiled spaces. My sister and I are thrilled that our kids have decided to do this and grateful to Sonoma Land Trust for making it happen. Through this transfer, we honor their great-grandfather by protecting the gift he gave them all those years ago.”

“When we sat down to explore options for the property, our first priority was not interfering with the natural habitat and feel of the area,” said Lucas Heldfond, grandson of Benjamin Swig and son of Patricia Dinner. “Working with Sonoma Land Trust has given us the opportunity to continue being responsible stewards and has helped realize our priority for keeping it as open space. They enabled us to meet our financial and tax goals without development, all while returning the land to public use – as it has been for most of time. It is heartening to us all that this land will remain open and will be an integral part of Sonoma Land Trust’s vision for a wildlife corridor that spans from the coast to the mountain ranges.”

Highlights

- Essential for conservation: Essential to meeting regional biodiversity goals identified in the Conservation Lands Network (CLN) analysis tool. The vernal pools and oak woodlands on the property support documented rare and threatened plant species.

- Regional Wildlife Corridor: A regionally significant wildlife corridor between Sonoma Mountain and Trione-Annadel State Park. This corridor adjoins the Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor and the Marin Coast-Blue Ridge Critical Linkage, connecting habitats in Pt. Reyes to the mountains of Napa and Lake Counties.

- Connects our parks: A significant step toward connecting the 6,200 adjacent protected acres around Annadel with over 9,000 protected acres to the south and east on Sonoma Mountain via a new segment of the Bay Area Ridge Trail.

- Riparian corridor and water: Supports recovery of the federally threatened Northern California steelhead by reducing threats to water quality, quantity, and temperature within Yulupa Creek, a tributary of Sonoma Creek.

- Climate resilience and carbon sequestration: Protects varied native vegetation, which has proven a critical component of wildfire resilience. In the 2017 Nuns Fire, portions of the property experienced low intensity burn without significant loss of oak trees, and the habitat and wildlife have since recovered.

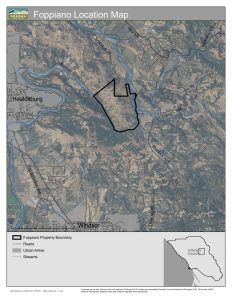

Sonoma Land Trust protects large Russian River ranch outside Healdsburg

More than a pretty place, Walter and Jean Foppiano Ranch offers extensive natural benefits

Sonoma Land Trust has protected one of the largest remaining ranches along the middle reach of the Russian River — a cattle ranch on a beautiful peninsula of rolling hills and grasslands one mile east of Healdsburg and bounded on three sides by the Russian River. On April 30, the Land Trust closed escrow on a conservation easement over the 758-acre Walter and Jean Foppiano Ranch belonging to their daughters, Ruth Ann Foppiano and Christine Foppiano Haun.

“My mother and father worked hard their whole life and were both very proud of the ranch,” says Haun. “They would be pleased with this result that my sister and I chose for it.”

“This charismatic ranch is really close to Healdsburg, but feels a world away,” says land acquisition program manager, Sara Press. “With an easement over this biologically rich property, we’re protecting the ecological function of an important stretch of the Russian River.”

The development risk in this part of the county is high. Under the conservation easement, which extinguishes the possibility of up to six estate homes and/or large-scale vineyards, the ranch’s meadows, woodlands and nearly three miles of river frontage and streamside habitat will remain undeveloped forever. The easement allows for sustainable grazing agriculture — a small herd of cattle will continue to graze peacefully there.

Protecting the ranch ensures that this landscape can continue to deliver its ecosystem benefits, including:

- filtering water that is part of a system that provides drinking water to more than 600,000 residents in Sonoma and Marin counties;

- recharging groundwater at a rate of 702 acre-feet per year, which is equivalent in volume to the annual water use of 3,600 households (Bay Area Greenprint); and

- storing almost 14,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas equivalent in the above-ground vegetation and over 40,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas equivalent in the soil (Bay Area Greenprint), which together are equivalent to the annual energy use of over 6,000 homes (EPA).

Recent history of the ranch In the mid-1950s, Walter Foppiano, his brother and sister purchased the original 1,600-acre ranch across from where the Maacama Creek converges with the Russian River. Over time, their families separated their holdings, ultimately leaving Christine and Ruth Ann with their parents’ 758-acre portion. Sonoma Land Trust’s purchase of a conservation easement over the property allows the ranch to remain as it has been for the last 70-plus years and to provide a vehicle to settle the estate.

“I enjoyed going out with my dad to help take care of the sheep and, in later years, cattle,” says Haun. “I learned how to ride a horse, to appreciate what needed to be done when caring for livestock and to have patience — and I came to realize just how lucky I was growing up as a child. My husband and I enjoy immensely being at the ranch every day just like my dad did.”

Property offers extensive biodiversity

The ranch is located within a wildlife movement corridor connecting Fitch Mountain and Modini Mayacamas Preserve, and its protection will provide enduring climate adaptation and resilience benefits for native plants and animals, including intact riparian (streamside) habitat and habitat connectivity. Thanks to unusual geology and hydrology at this site, the Russian River makes a big loop around the property, surrounding it on three sides. The ample water and undeveloped nature of the ranch benefits numerous species of wildlife — even mountain lion tracks have been seen from time to time along the sandy riverbank.

Conserving this property will also help protect at-risk aquatic species that include Coho salmon, steelhead trout, California freshwater shrimp, red-legged frog and foothill yellow-legged frog. The entire ranch is considered essential for conservation by the Conservation Lands Network, a respected regional conservation strategy for the San Francisco Bay Area.

Funding for easement purchase

Funding to purchase the conservation easement was secured from the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Agricultural Conservation Easement Program; the California Strategic Growth Council’s Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation program with funds from California Climate Investments, a statewide initiative that puts billions of Cap-and-Trade dollars to work; and the Bay Area Conservation Small Grants Program of Resources Legacy Fund, which is funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

“Congratulations to the Foppiano family and the Sonoma Land Trust for protecting the Foppiano Ranch forever,” says Jessica Buendia, acting executive director of the California Strategic Growth Council, which supported the land acquisition with an award through its Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program. “Protecting these 758 acres is a powerful example of how actions with major local benefits help advance important State goals to reduce and avoid greenhouse gas emissions, to protect and recharge groundwater, and to conserve natural and working lands.”

A Force for Nature Campaign

Protecting this property along the Russian River is a project of the $80 million “A Force for Nature” fundraising campaign that Sonoma Land Trust will launch publicly on May 25, 2021. The campaign funds land protection work, such as the Foppiano Ranch project, as well as other nature-based projects and programs aimed at fostering climate resilience. Thanks to generous support from individuals, businesses, foundations and government entities, we are more than 70 percent of the way to reaching the goal. Join us May 25 to learn more about the campaign. https://give.sonomalandtrust.org/forcefornature

# # #

About Sonoma Land Trust

Sonoma Land Trust works in alliance with nature to conserve and restore the integrity of the land with a focus on climate resiliency and is also committed to ensuring more equitable access to the outdoors. Since 1976, Sonoma Land Trust has protected more than 56,000 acres of scenic, natural, agricultural and open land for future generations. Sonoma Land Trust is the recipient of the 2019 Land Trust Alliance Award of Excellence and is accredited by the Land Trust Accreditation Commission. For more information, please visit www.sonomalandtrust.org.

About NRCS’ Sonoma County Venture Conservation Regional Conservation Partnership Program

NRCS’ Sonoma County Venture Conservation (SCVC) Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) is a collaboration of partners, funders, residents, farmers and ranchers working to conserve and restore land in Sonoma County to ensure resilience to climate change through healthy soils, high-quality surface and groundwater supplies, healthy habitat for fish and wildlife, and a thriving agricultural industry. The Partnership received a five-year $8,049,000 grant for activities such as protecting agricultural land through conservation easements. For more information about RCPP, visit https://www.sonomaopenspace.org/projects/sonoma-county-venture-conservation-partnership/.

About Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program

The Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program (SALC), a component of the California Strategic Growth Council’s Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC) Program, supports California’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction goals by making strategic investments to protect agricultural lands from conversion to more GHG-intensive uses. Protecting critical agricultural lands from conversion to urban or rural residential development encourages infill development within existing jurisdictions, ensures open space remains available, and supports a healthy agricultural economy and resulting food security. A healthy and resilient agricultural sector is a critical part of meeting the challenges occurring and anticipated as a result of climate change.

Administered by the Department of Conservation’s Division of Land Resource Protection, SALC is part of California Climate Investments, a statewide program that puts billions of Cap-and-Trade dollars to work reducing GHG emissions, strengthening the economy, and improving public health and the environment — particularly in disadvantaged communities. The Cap-and-Trade program also creates a financial incentive for industries to invest in clean technologies and develop innovative ways to reduce pollution. California Climate Investments projects include affordable housing, renewable energy, public transportation, zero-emission vehicles, environmental restoration, more sustainable agriculture, recycling, and much more. At least 35 percent of these investments are located within and benefiting residents of disadvantaged communities, low-income communities, and low-income households across California. For more information, visit the California Climate Investments website at: www.caclimateinvestments.ca.gov.

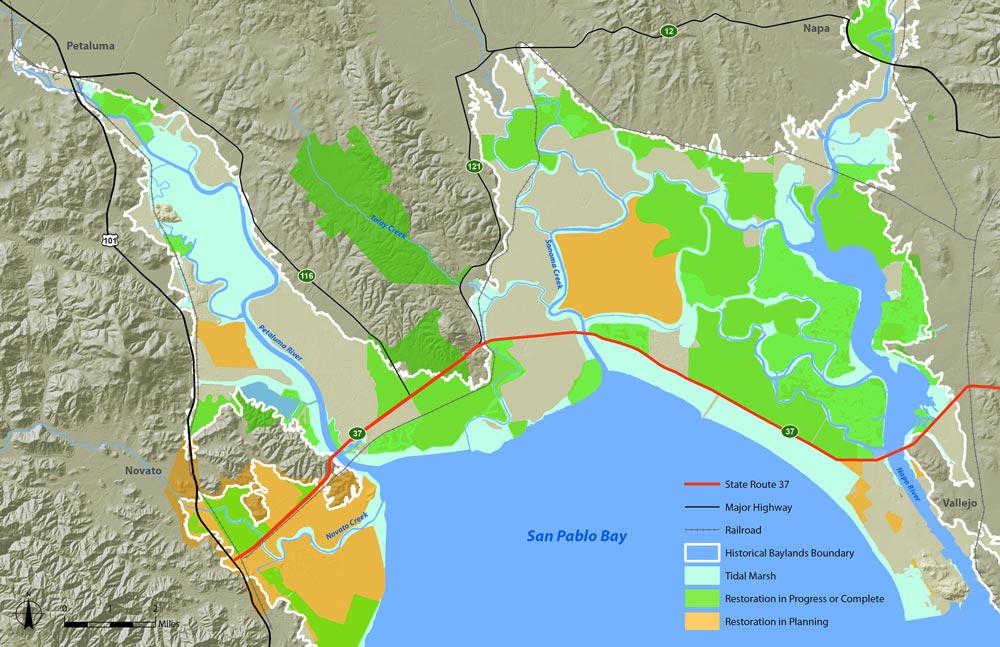

Return of the Baylands

Helping Water Go with the Flow in the Sonoma Creek Baylands

The picturesque landscape of the Sonoma Creek Baylands hides a secret: they’re in dire straits. Now, Sonoma Land Trust and their partners are embarking on a landscape-scale restoration that will restore marshes and reconnect upland streams to their historic tidal wetlands, some for the first time in over a century. From the “Stage Zero” Lakeville Creek restoration project to upgrading a bridge on State Route 37, learn from Emily Harwitz how Sonoma Land Trust is helping coastal ecosystems and communities adapt to rising sea levels.

It’s a windy day in Sonoma County as Julian Meisler stands atop a grassy hill overlooking Lakeville Creek, gazing at open pastures beyond, some dotted with cattle, toward the busy State Route 37, then the Petaluma River Baylands, and finally the glinting waters of San Pablo Bay. “You look out here and it’s very pretty and pastoral,” says Meisler, Sonoma Land Trust’s Baylands program manager, “but one of the big surprises to me when I started working here was—wow—this is a highly manipulated and highly managed landscape.”

Less than two centuries ago, these dry flatlands were wet baylands. Freshwater creeks flowed downhill, fanning out once they reached the flat ground near the bay’s marshes and depositing nutrient-rich sediment along San Pablo Bay’s northern edge. In these baylands, vast salt marshes flourished, creating habitat for a unique and diverse array of wildlife. These wetlands secured the shoreline, shielding it from erosion caused by storm surges and high tides.

Then, in the nineteenth century, these wetlands became the target of agricultural development. Incentivized by the federal Swampland Act of 1850, landowners diked and drained thousands of acres into parcels of agricultural land. This effectively cut off the North Bay’s watersheds from reaching the San Pablo Bay.

“Most streams that once connected to the bay don’t anymore,” says Meisler. “They flow into ditches and detention ponds and then they’re pumped over levees.” What used to be a vast tapestry of tidal and seasonal wetlands is now a mosaic of flood-prone, privately managed tracts of land, plus a bay depleted of necessary sediment. With climate change, sea levels are rising, wet winter storms are becoming more extreme, and the cost to farmers of maintaining the pumps is only increasing. “It’s very, very precarious,” he says.

But this fragmented bayland is in the middle of a hopeful transformation. Sonoma Land Trust and their partners are planning a 6,000-acre landscape-scale restoration that will restore marshes and reconnect upland streams to their historic tidal wetlands. It’s part of the Sonoma Creek Baylands Strategy that aims to protect and restore 10,000 acres of bayland and adjacent lands by 2030. The goal is to rehabilitate the baylands and build climate resiliency back into the landscape, buffering against rising sea levels, floods, wildfire, and drought, while bringing back habitat for threatened species and creating new opportunities for the public to access nature along the bay.

Restoring Lakeville Creek, which connects the watershed on the hills of Sears Point Ranch to the historic bay margin, is a key piece of the plan. The restoration, funded by a $2.2 million grant from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, is being guided by a cutting-edge “Stage Zero” approach. It’s the first restoration of its kind in the Bay Area, which looks at restoring not just the stream, but the natural processes in the entire stream valley.

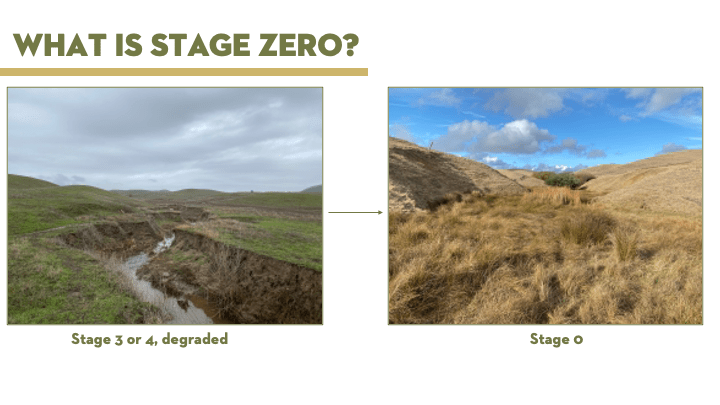

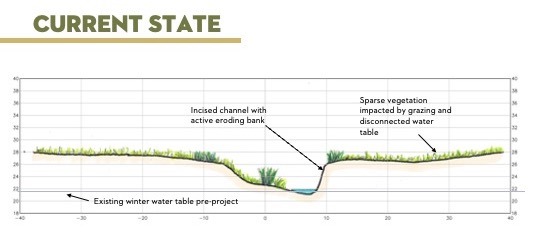

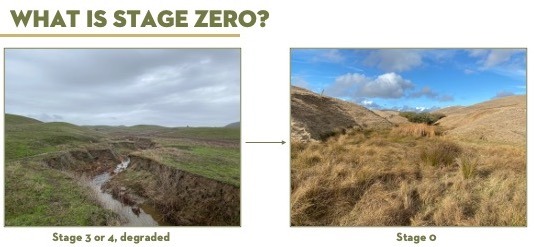

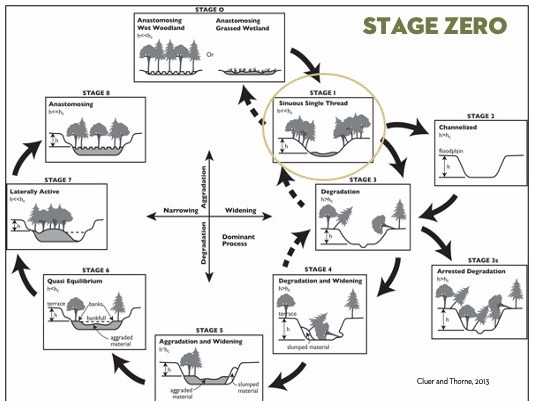

Before restoration began, Lakeville Creek was much like many eroded creek beds found throughout the West; deeply carved with steep, balding banks. When water flows through these eroded channels, it moves too quickly to penetrate into the soil, disconnecting it from its natural floodplain and exacerbating flooding downstream.

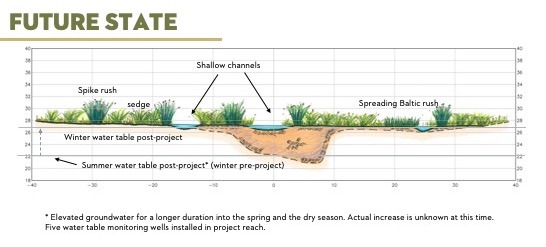

In Stage Zero, referring to the pre-channelized state, a creek looks more like a wet meadow than a distinct flowing stream. Dense wetland vegetation anchors sediment and slows the flow of water enough so that it can spread out and saturate the ground, replenishing aquifers and allowing the soil to stay moist through dry seasons. This wet landscape supports habitat for a diverse array of plants and wildlife.

As Meisler stands on it today, 6 months after the first earth mover trundled onto the site, Lakeville Creek is already well on its way toward achieving a Stage Zero state. With their partners, Prunuske Chatham Incorporated (PCI), restoration began by filling in the channel with nine hundred dump trucks of soil from a nearby site to recreate the level meadow of its past. In December, with the help of the Watershed, Walker, and Laguna nurseries, the restoration team placed the first round of what will eventually be 35,000 plants into the ground.

A chorus of Sierran treefrogs ribbits in the filled-in wet creek valley and Meisler hopes they will soon be joined by the threatened California red-legged frog which Sonoma Land Trust built breeding ponds for in a neighboring valley. “Rehabilitating stream corridors is building wildlife movement corridors,” he says, “so we’re hoping we can give the frog someplace to move.”

Over Cougar Mountain to the east lies Tolay Creek Bridge on State Route (SR) 37, another key piece of the baylands restoration puzzle. As it stands, Tolay Creek Bridge spans most of the channel opening between Tolay Creek and the Sonoma Baylands. It’s the pinch point preventing vital sediment-laden tidal waters from reaching the rest of Tolay Creek’s historic baylands. It also blocks wildlife from moving underneath it.

To restore the free flow of water and wildlife, the channel will have to be widened by lengthening the bridge that currently cuts through it. It’s a massive infrastructure project, but Sonoma Land Trust isn’t the only stakeholder that wants to upgrade Tolay Creek Bridge. Improving SR 37 is a priority for transportation agencies as the bridge faces daily congestion from the over 40,000 commuters who drive across it each day. The entire length of SR 37 also faces increasingly frequent flooding from sea level rise.

What should be an opening of several hundred feet wide is about 60 feet because of the way that bridge is currently built. In an ideal world, Meisler says, SR 37 from Sears Point to Mare Island would be raised on a causeway. However, due to funding constraints, that isn’t likely to happen until after 2041, when models suggest the roadway will be permanently underwater. “In the meantime,” he says, “our main goal is less about ‘can we influence exactly how this road is built,’ but about ‘how do we make sure we can restore marshes before the pace of sea level rise increases and makes successful restoration far more difficult?’”

The timing element is crucial. If sediment can build up now before sea levels rise even more, wetland plants can establish on ground that’s high enough to survive rising water levels in the future. That, in turn, will slow shoreline erosion and buffer against flooding and sea level rise, absorbing wind and wave impact from storms and rooting sediment down.

In 2017, Sonoma Land Trust and the State Coastal Conservancy convened the State Route 37-Baylands Group to advocate for wetland restoration to be integrated into all SR 37 improvement projects, including the Tolay Creek Bridge expansion. Comprised of North Bay habitat restoration practitioners, baylands land managers, and other stakeholders, the group works closely with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, regional transportation agencies, and Caltrans to ensure that SR 37’s redesign integrates restoration goals alongside transportation needs.

Last December, the California Transportation Commission approved a $50 million grant to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission to support this project. More recently in February, the State Coastal Conservancy approved $1.2 million for SLT for the Tolay Creek watershed restoration planning. Initially, transportation agencies balked at the addition of lengthening the bridge in addition to expanding it, thinking it too costly to consider. But the SR 37-Baylands Group successfully made the case that, without lengthening the bridge and thereby opening up the Tolay Creek channel, the baylands upstream could not be restored. While Sonoma Land Trust still has to raise funds to acquire land and do the restoration work—no easy task in the current political climate—having the funds for planning and environmental commitments from the transportation agencies is a great start, says Ariana Rickard, Public Policy and Funding Program Manager at Sonoma Land Trust. “The most exciting thing is that we are going forward,” she says.

“As we experience sea level rise in many places, it’ll be really important to have these kinds of integrated planning processes that consider the natural environment and the need for it to adapt to climate change, as well as our built environment adapting to climate change,” says Jessica Davenport, Deputy Program Manager at the State Coastal Conservancy who leads the State Route 37-Baylands Group.

Looking out over the baylands, it’s easy to see the human-made divisions between the bay and the uplands—levees, railroad tracks, roads. In other regions, there might be malls, airports, and cities. But it’s also possible to envision the connected landscape, upland streams to baylands to the bay. If we can observe the natural processes occurring and understand the cycles of nature, perhaps we can restore our connection to the landscape, too.

“Here, we have some development but not that much. That’s what makes this landscape such a promising one,” Meisler says, “this kind of large scale, 10,000-acre restoration—it’s so possible, totally achievable, and I’m sure we’re gonna get it.”

Lakeville Creek Restoration Project

Restoring to Stage Zero on Sears Point Preserve

Sonoma Land Trust is recharging groundwater aquifers, protecting biodiversity, and supporting climate-ready ecosystems, one stage at a time.

Restoration work started in August 2023, filling the channel was completed in the fall, and planting started in December 2023.

Introduction

A creek restoration approach called “Stage Zero” is making its Bay Area debut. The restoration project will rehabilitate a 4,200-foot reach of Lakeville Creek, a seasonal tributary to the Petaluma River that links the watershed on the hills of Sears Point Ranch, to the historic water’s edge of the San Pablo Bay. Sonoma Land Trust was awarded $2.2 million from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) for this project and will be initiating the work this summer with Prunuske Chatham, Inc (PCI), ecological consultants.

Lakeville Creek is not a creek you might have heard of or can easily spot on a map. It’s a deeply eroded channel that developed over a century of heavy grazing and other land uses on the slopes of the 1,142-acre Sears Point Ranch Preserve. At one time, this seasonal creek valley supported dense wetland vegetation from its upper reaches to the historic bay margin (the boundary used to identify where the bay previously met the land).

Julian Meisler, Sonoma Land Trust’s Baylands program manager, is leading this endeavor and shared his thoughts. “Stream valley restoration projects will become increasingly common in similar settings within California in the coming years because they are effective in restoring the natural processes that make us more resilient to climate change. By returning the missing elements and giving them the time and space to work, the land can capture and store water to help sustain us through droughts, provide moisture for habitats to support wildlife and those habitats become more resilient to wildfires by remaining wetter longer.”

Sears Point Preserve

He added, “Back in the early 2000s, Sonoma Land Trust saw an opportunity at the 2,327-acre Sears Point Preserve to positively influence every raindrop from the sky to the bay by protecting and restoring this small watershed. It was purchased specifically for that reason, to restore the grasslands, streams, tidal wetlands, and the processes that connect them. This means connecting habitats for the burrowing owls and silverspot butterflies of the grasslands, red-legged frogs of the freshwater wetlands, and the ridgway rails and shorebirds of the tidal wetlands.”

This project will build upon Sonoma Land Trust’s two-decades of extensive, landscape-scale wetland restoration program in the baylands using the most successful technology available – nature-based solutions. This project is impressive in scale in that it requires moving nine hundred dump trucks of dirt to fill the eroded channel, adds thirty thousand native plants to create habitat for threatened species, and increases climate resilience that addresses sea level rise, wildfire, and drought.

Transitioning to a thriving ecosystem

Lakeville Creek looks very much like other eroded ditches found throughout Sonoma County and the American west. These eroded waterways are problematic and are drawing the attention of restoration practitioners because they drain water quickly off the land before it can sink into the soil, recharge aquifers, and hydrate habitat that can resist drought in dry seasons. Simply stated, they exacerbate flooding, increase susceptibility to wildfire, and prevent wetland vegetation from developing, leaving no place for the species that rely on them, such as the threatened California red-legged frog. These wetland or riparian ecosystems are incredibly valuable and provide filtered water, carbon sinks, and more importantly, they support a greater variety of biodiversity (plants, fish, birds, etc.) and are home to more threatened and endangered species than any other habitat in California. Restoring our remaining wetlands is a key component to creating a buffer from the worst effects of climate change.

Conceiving of Stage Zero took time but is quickly being adopted

It may come as no surprise to learn that this new concept for creek restoration was co-authored by a NOAA scientist who lives right here in Sonoma County. Brian Cluer is a scientist who has studied the degraded states of streams, creeks, floodplains, and wetlands here in our county and in the Pacific Northwest. In an influential paper published over a decade ago with Colin Thorne, an environmental scientist from the United Kingdom, Brian argued that the eight stages of creek evolution were not comprehensive enough and lacked the preliminary state present in some streams, something that is now referred to as “Stage Zero.” They explain in the paper that a preceding stage in these types of creeks looks more like a wet meadow than a flowing stream and is comprised of dense wetland vegetation with multiple low swales running through it, instead of a single channel. These swales are marshy depressions in the stream valley that you might not even notice unless you tried to walk across them. Because the Stage Zero wetland holds moisture over longer periods of time, it recharges ground water supplies and sustains ecosystems for wildlife while also reducing the risk of wildfire.

“River [and stream] restoration has evolved in the last decade to consider the valley that a channel is part of. Valley restoration has become common in Oregon and recently in mountain meadows in the Sierra’s, but this will be the first valley restoration following the concept of Stage Zero in the Bay Area,” said Brian Cluer. “We expect the water table to recover by filling the incised channel and a higher water table will support a much larger wetland complex that will be more resilient to drought.”

Preparing for Climate Change

In the coming decades, California is projected to continue to warm, heat waves will increase in intensity and duration, sea level will rise several feet, and extreme storms and droughts are expected to become more frequent. The San Pablo Bay will be impacted by all these stressors, as acknowledged in the 2015 Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals Science Update. One of the primary recommendations of the 2015 report is to restore complete ecosystems by connecting tidal ecosystems to their upland watersheds.

How did Sonoma Land Trust discover the concept for Stage Zero?

Though the concept of Stage Zero builds on decades of academic study and field research, the idea to bring it to Lakeville Creek emerged when Sonoma Land Trust staff and restoration partners discovered that the creek upstream from the Sears Point Preserve on Sonoma Raceway’s property presented the textbook characteristics of a Stage Zero creek valley. It was vastly different than the 4,200 feet of the eroded Lakeville Creek channel and confirmed that this new approach to restoration held its promise to create a functioning system that achieved the goals we were aiming for.

After studying the property with the design team at Prunuske Chatham, Inc. (PCI), we pursued funding for a design based on the Stage Zero concept. Brian Cluer, the NOAA scientist and co-author of the paper on Stage Zero restorations, agreed to join our technical working group and confirmed that the site was appropriate for this new approach to restoration and he pulled in Paul Powers from United States Forest Service to join the team. Together, Brian, Paul, PCI, staff from the land trust, and a technical working group composed of regulatory agencies worked on the design, applied for the permits, and were recently awarded $2.2 million by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for construction. The project received a statutory exemption from CEQA as part of California’s Cutting the Green Tape initiative to fast-track restoration projects that meet their criteria and has received input from the local tribes required for the exemption. This project was the second project in the state to be successfully awarded this exemption.

What will construction look like?

Restoring thousands of feet of eroded stream channel to a Stage Zero wet meadow requires filling it in with nearly nine hundred dump trucks of soil. Importing soil is prohibitively expensive, but fortunately, careful analysis by PCI identified several hillsides adjacent to the creek had been sculpted by bulldozers many decades ago to try to stop hillside erosion. The dirt that was moved in that process was pushed into the creek in the upper segment of the project area. Conveniently, we will move that soil to fill the eroded sections and provide a rebalancing of the landscape throughout the project area using materials already close at hand.

Credit: Cat Chang

Credit: Colby Hines

Biodiversity wins!

To stabilize the soil and to create the future habitat will require planting of tens of thousands of native wetland plants and willows, re-seeding of disturbed areas, and protecting the vegetation already in the area. This includes taking special consideration to protect existing populations of Viola pedunculata (also known as the California Golden Violet, or as the johnny jump up) which is the larval host plant for the callippe silverspot butterfly (Speyeria callippe callippe), a federally recognized endangered species. The only population of callippe silverspot butterfly in Sonoma County is reported in the project vicinity and additional johnny jump up plants will be added to expand the host plant population for the butterfly. In addition, nectar-producing plants are also included in the project revegetation plans to expand food sources for the butterfly across the project area.

A monitoring schedule over a minimum of five years will be required to track how the vegetation takes hold and the changes to the water table levels. If the project is successful, monitoring reports will track significantly higher water table levels in the summer which will sustain the new habitat through future droughts. In the long-term we expect to see a variety of wildlife using this habitat for shelter, foraging, and as a corridor between the baylands and the uplands.

Additional information about Stage Zero projects can be found: http://stagezeroriverrestoration.com/index.html