Return of the Baylands

Helping Water Go with the Flow in the Sonoma Creek Baylands

The picturesque landscape of the Sonoma Creek Baylands hides a secret: they’re in dire straits. Now, Sonoma Land Trust and their partners are embarking on a landscape-scale restoration that will restore marshes and reconnect upland streams to their historic tidal wetlands, some for the first time in over a century. From the “Stage Zero” Lakeville Creek restoration project to upgrading a bridge on State Route 37, learn from Emily Harwitz how Sonoma Land Trust is helping coastal ecosystems and communities adapt to rising sea levels.

It’s a windy day in Sonoma County as Julian Meisler stands atop a grassy hill overlooking Lakeville Creek, gazing at open pastures beyond, some dotted with cattle, toward the busy State Route 37, then the Petaluma River Baylands, and finally the glinting waters of San Pablo Bay. “You look out here and it’s very pretty and pastoral,” says Meisler, Sonoma Land Trust’s Baylands program manager, “but one of the big surprises to me when I started working here was—wow—this is a highly manipulated and highly managed landscape.”

Less than two centuries ago, these dry flatlands were wet baylands. Freshwater creeks flowed downhill, fanning out once they reached the flat ground near the bay’s marshes and depositing nutrient-rich sediment along San Pablo Bay’s northern edge. In these baylands, vast salt marshes flourished, creating habitat for a unique and diverse array of wildlife. These wetlands secured the shoreline, shielding it from erosion caused by storm surges and high tides.

Then, in the nineteenth century, these wetlands became the target of agricultural development. Incentivized by the federal Swampland Act of 1850, landowners diked and drained thousands of acres into parcels of agricultural land. This effectively cut off the North Bay’s watersheds from reaching the San Pablo Bay.

“Most streams that once connected to the bay don’t anymore,” says Meisler. “They flow into ditches and detention ponds and then they’re pumped over levees.” What used to be a vast tapestry of tidal and seasonal wetlands is now a mosaic of flood-prone, privately managed tracts of land, plus a bay depleted of necessary sediment. With climate change, sea levels are rising, wet winter storms are becoming more extreme, and the cost to farmers of maintaining the pumps is only increasing. “It’s very, very precarious,” he says.

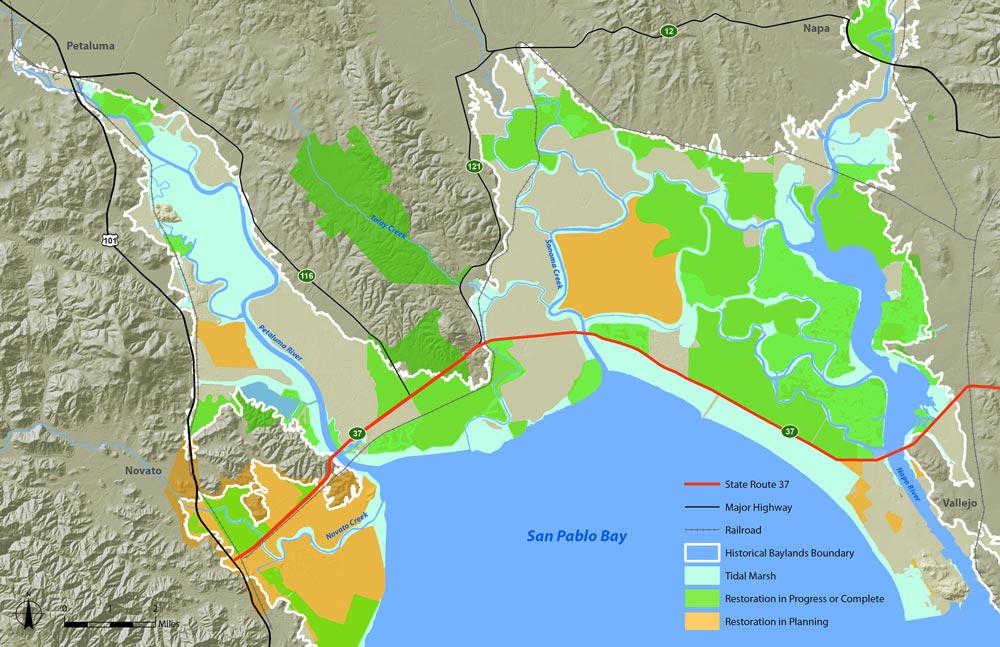

But this fragmented bayland is in the middle of a hopeful transformation. Sonoma Land Trust and their partners are planning a 6,000-acre landscape-scale restoration that will restore marshes and reconnect upland streams to their historic tidal wetlands. It’s part of the Sonoma Creek Baylands Strategy that aims to protect and restore 10,000 acres of bayland and adjacent lands by 2030. The goal is to rehabilitate the baylands and build climate resiliency back into the landscape, buffering against rising sea levels, floods, wildfire, and drought, while bringing back habitat for threatened species and creating new opportunities for the public to access nature along the bay.

Restoring Lakeville Creek, which connects the watershed on the hills of Sears Point Ranch to the historic bay margin, is a key piece of the plan. The restoration, funded by a $2.2 million grant from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, is being guided by a cutting-edge “Stage Zero” approach. It’s the first restoration of its kind in the Bay Area, which looks at restoring not just the stream, but the natural processes in the entire stream valley.

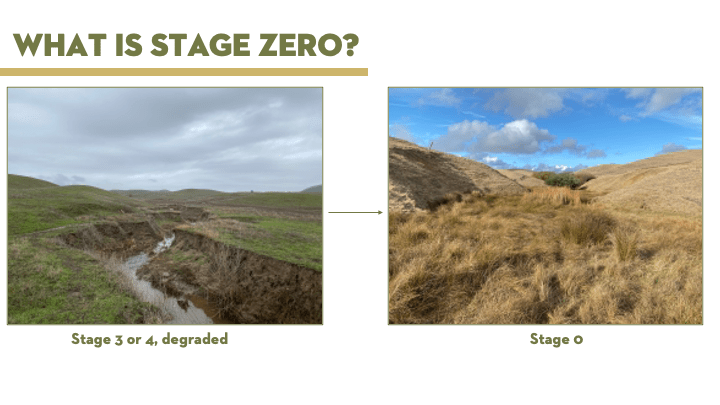

Before restoration began, Lakeville Creek was much like many eroded creek beds found throughout the West; deeply carved with steep, balding banks. When water flows through these eroded channels, it moves too quickly to penetrate into the soil, disconnecting it from its natural floodplain and exacerbating flooding downstream.

In Stage Zero, referring to the pre-channelized state, a creek looks more like a wet meadow than a distinct flowing stream. Dense wetland vegetation anchors sediment and slows the flow of water enough so that it can spread out and saturate the ground, replenishing aquifers and allowing the soil to stay moist through dry seasons. This wet landscape supports habitat for a diverse array of plants and wildlife.

As Meisler stands on it today, 6 months after the first earth mover trundled onto the site, Lakeville Creek is already well on its way toward achieving a Stage Zero state. With their partners, Prunuske Chatham Incorporated (PCI), restoration began by filling in the channel with nine hundred dump trucks of soil from a nearby site to recreate the level meadow of its past. In December, with the help of the Watershed, Walker, and Laguna nurseries, the restoration team placed the first round of what will eventually be 35,000 plants into the ground.

A chorus of Sierran treefrogs ribbits in the filled-in wet creek valley and Meisler hopes they will soon be joined by the threatened California red-legged frog which Sonoma Land Trust built breeding ponds for in a neighboring valley. “Rehabilitating stream corridors is building wildlife movement corridors,” he says, “so we’re hoping we can give the frog someplace to move.”

Over Cougar Mountain to the east lies Tolay Creek Bridge on State Route (SR) 37, another key piece of the baylands restoration puzzle. As it stands, Tolay Creek Bridge spans most of the channel opening between Tolay Creek and the Sonoma Baylands. It’s the pinch point preventing vital sediment-laden tidal waters from reaching the rest of Tolay Creek’s historic baylands. It also blocks wildlife from moving underneath it.

To restore the free flow of water and wildlife, the channel will have to be widened by lengthening the bridge that currently cuts through it. It’s a massive infrastructure project, but Sonoma Land Trust isn’t the only stakeholder that wants to upgrade Tolay Creek Bridge. Improving SR 37 is a priority for transportation agencies as the bridge faces daily congestion from the over 40,000 commuters who drive across it each day. The entire length of SR 37 also faces increasingly frequent flooding from sea level rise.

What should be an opening of several hundred feet wide is about 60 feet because of the way that bridge is currently built. In an ideal world, Meisler says, SR 37 from Sears Point to Mare Island would be raised on a causeway. However, due to funding constraints, that isn’t likely to happen until after 2041, when models suggest the roadway will be permanently underwater. “In the meantime,” he says, “our main goal is less about ‘can we influence exactly how this road is built,’ but about ‘how do we make sure we can restore marshes before the pace of sea level rise increases and makes successful restoration far more difficult?’”

The timing element is crucial. If sediment can build up now before sea levels rise even more, wetland plants can establish on ground that’s high enough to survive rising water levels in the future. That, in turn, will slow shoreline erosion and buffer against flooding and sea level rise, absorbing wind and wave impact from storms and rooting sediment down.

In 2017, Sonoma Land Trust and the State Coastal Conservancy convened the State Route 37-Baylands Group to advocate for wetland restoration to be integrated into all SR 37 improvement projects, including the Tolay Creek Bridge expansion. Comprised of North Bay habitat restoration practitioners, baylands land managers, and other stakeholders, the group works closely with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, regional transportation agencies, and Caltrans to ensure that SR 37’s redesign integrates restoration goals alongside transportation needs.

Last December, the California Transportation Commission approved a $50 million grant to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission to support this project. More recently in February, the State Coastal Conservancy approved $1.2 million for SLT for the Tolay Creek watershed restoration planning. Initially, transportation agencies balked at the addition of lengthening the bridge in addition to expanding it, thinking it too costly to consider. But the SR 37-Baylands Group successfully made the case that, without lengthening the bridge and thereby opening up the Tolay Creek channel, the baylands upstream could not be restored. While Sonoma Land Trust still has to raise funds to acquire land and do the restoration work—no easy task in the current political climate—having the funds for planning and environmental commitments from the transportation agencies is a great start, says Ariana Rickard, Public Policy and Funding Program Manager at Sonoma Land Trust. “The most exciting thing is that we are going forward,” she says.

“As we experience sea level rise in many places, it’ll be really important to have these kinds of integrated planning processes that consider the natural environment and the need for it to adapt to climate change, as well as our built environment adapting to climate change,” says Jessica Davenport, Deputy Program Manager at the State Coastal Conservancy who leads the State Route 37-Baylands Group.

Looking out over the baylands, it’s easy to see the human-made divisions between the bay and the uplands—levees, railroad tracks, roads. In other regions, there might be malls, airports, and cities. But it’s also possible to envision the connected landscape, upland streams to baylands to the bay. If we can observe the natural processes occurring and understand the cycles of nature, perhaps we can restore our connection to the landscape, too.

“Here, we have some development but not that much. That’s what makes this landscape such a promising one,” Meisler says, “this kind of large scale, 10,000-acre restoration—it’s so possible, totally achievable, and I’m sure we’re gonna get it.”