The Right of Passage: Restoring Wildlife Movement in Sonoma Valley

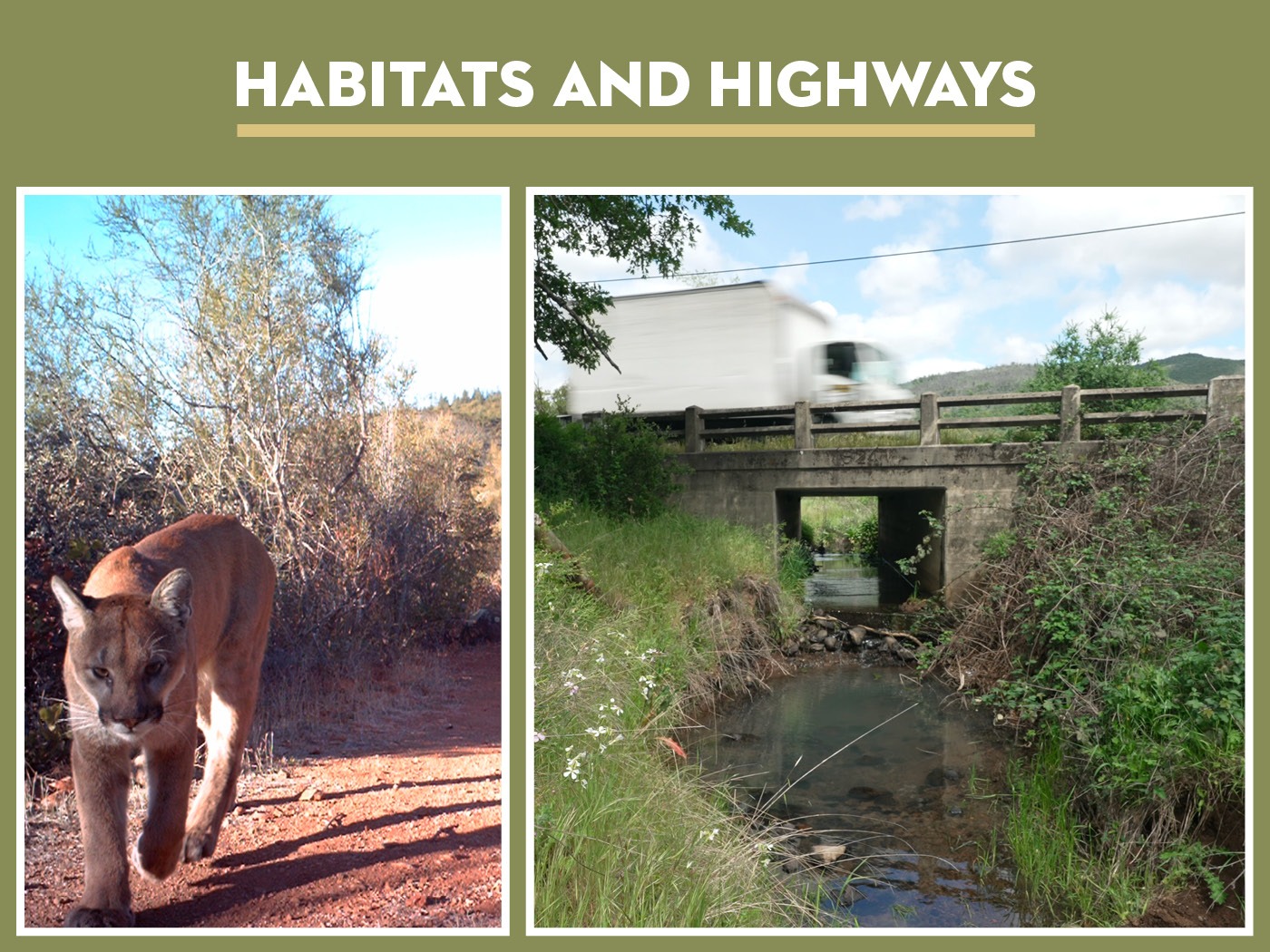

In Sonoma Valley, forested hills, meandering creeks, open grasslands, and oak woodlands stretch across the landscape. So does Highway 12. Although we usually think of the Glen Ellen area as the heart of the Wildlife Corridor, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has identified nearly the entire valley, including the 13 miles of Hwy 12, as a barrier to wildlife movement. To determine where wildlife are crossing—or attempting to cross—the road, stewardship program manager Chris Carlson is launching a study to collect key data needed to understand what kind of movement improvements would have the greatest impact. That includes where these efforts are needed and what kinds of infrastructure or habitat improvement would help the greatest number of animals. Options might include overhead crossings, directional fencing to guide animals, or improvements to existing culverts so more species feel safe to use them. California Department of Fish and Wildlife and CalTrans have staffed up their wildlife connectivity program and are partnering with us on the new effort.

Over the last decade, our understanding of wildlife movement through the Sonoma Wildlife Corridor has evolved dramatically. For one, our seminal wildlife camera study in 2014 showed us the surprising plethora of animals using underpasses to cross the road—even a family of river otters! One of the biggest learnings, though, has been seeing how different animals make different choices based on their individual needs. For example, most mountain lions prefer to move through riparian corridors, which offer food, water, and cover, rather than across open grasslands. Adjacent lands must be connected by healthy habitat that makes sense for animals to travel through, not just sit side by side on a map. “You can do a landscape model, but unless you’re zooming in to a local level, it’s hard to know the best place to make conservation investments,” Chris says. “Fine-scale knowledge of local places is important.”

Even in an industrialized, modern world, animals are still finding ways to move across the landscape. Movement—for food, water, shelter, mates, or new territory—is a basic requirement of life. Yet across California, fences, roads, bright lights, noise, and sprawl increasingly block their paths. As climate change and development force species to shift their ranges, the ability to move freely through connected landscapes has never been more critical. In 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom launched the California Wildlife Reconnected initiative alongside state agencies and nonprofits to boost connectivity initiatives across the state, stating that connectivity is a key part of California’s 30×30 commitment.

When pathways are cut off, finding new ones presents immediate and long-term challenges. In the moment, wildlife have to use extra energy to avoid human activity like a busy road or even a well-trafficked trail. Over time, their altered behaviors and interactions can lead to increased stress, reduced fitness, genetic isolation, or even extirpation (local extinction). Populations confined to small, fragmented areas collapse when they outgrow the resources available. Physical barriers like tall or poorly designed fences may block migrations entirely, while clogged underpasses make once-viable routes more dangerous. One reason for that is the interspecies traffic jam. Studies have shown that mule deer avoid underpasses frequently used by mountain lions, and coyotes favored underpasses frequently used by small mammals like rodents and hares. Life is hard when you have to choose between the odds of getting squished by a car or eaten.

Fortunately, solutions exist. Large-scale wildlife crossings, like the Wallis Annenberg Crossing in Los Angeles, can be critical passageways, especially for larger animals, across major roads. When possible, though, it’s better to have many smaller crossings than one huge one. That way, animals have more options to choose from when making survival decisions for themselves. Closer to home, protecting and restoring wildlife corridors is just as vital. The Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor connects Sonoma Mountain across the valley floor to the Mayacamas range, bridging the Marin Coast and the Blue Ridge–Berryessa region. Since 1976, Sonoma Land Trust has protected more than 8,000 acres here, secured at-risk parcels in critical pinch points, and developed a long-term monitoring and management strategy to keep the corridor permeable for wildlife.

Another major part of the solution is addressing outdated fencing. Across our lands, we’re either removing fences or replacing them with wildlife-friendly designs that allow animals to pass through while still managing livestock. “It’s one of the most impactful ways private landowners can support healthy wildlife corridors,” says stewardship program manager Tom Tolliver, “and we encourage anyone who can to do the same.” Recently, we replaced a significant stretch of old fencing at Laufenburg Ranch and have more work planned for Pole Mountain.

By restoring habitat, replacing barriers, and studying wildlife movement in detail, we’re ensuring that animals in Sonoma Valley and beyond have the room they need to move, adapt, and thrive. Thank you to our dedicated volunteers whose hard work makes these on-the-ground changes possible.

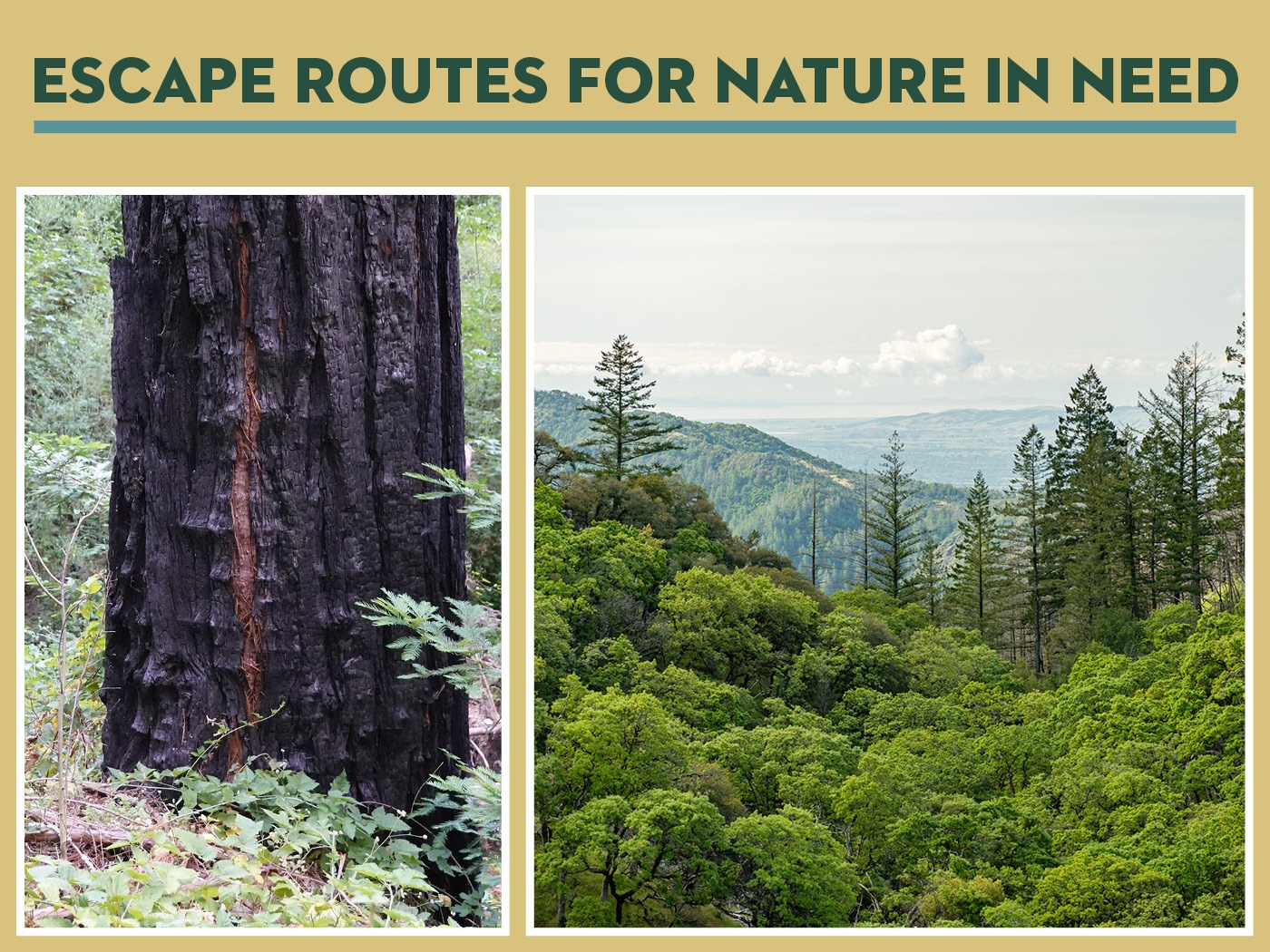

How plants move to survive a changing climate

As climate change touches every corner of Earth, plants and trees face a stark choice: move, adapt quickly, or vanish. Redwoods, for instance, may be losing the moist fog they depend on in some parts of their range. If they’re to survive the hotter, drier summers of the future, they’ll need the option to migrate towards cooler slopes, fog-wrapped ridges, and valleys rich with water. Without connected pathways to reach these refuges, even giants may falter. And when plants are stuck in place, the creatures who depend on them may be out of luck, too.

Consider the finely tuned relationship between our state butterfly and its host plant California false indigo (Amorpha californica). The California dogface butterfly (Zerene eurydice) depends almost entirely on California false indigo as its host plant to lay eggs and rear larvae. False indigo, in turn, needs fire to germinate its seeds. In Sonoma County, we have a small population of the northern false indigo, but without connected lands that get periodic fire, the false indigo seeds will have nowhere to go where they can germinate to sustain, or even grow, the population. And if this plant disappears, so too will the dogface butterfly. Returning fire to the land is one crucial way to help our fire-adapted plant species have access to suitable ground. These highly interconnected ecological relationships are what Sonoma Land Trust’s stewardship team considers when prioritizing how to restore and steward plant habitats.

Like animals, plants have always relied on movement to survive. Though they lack legs or wings, their populations spread through ingenious forms of seed dispersal—or, in the case of redwoods, clonal sprouting. Seeds may float downstream, ride a gust of wind, cling to animal fur, or wait for fire to release them from resin-sealed cones. Some plants, like lupines and poppies, catapult their seeds with miniature spring-loaded mechanisms, while others extend roots or stems to inch toward water or nutrient-rich soil.

But in today’s industrially altered world, that natural movement isn’t always enough. As habitats become too hot, dry, or fragmented by roads, fences, and development, plants struggle to keep pace. Unlike hardy generalists such as Scotch broom, most native species are specialists, evolved to thrive with certain soils, fungi, pollinators, and climate patterns. If those conditions vanish and there’s no clear path to new territory, plants—and the creatures that depend on them—risk disappearing altogether.

That’s why Sonoma Land Trust is working to secure connected, resilient landscapes. Protecting large tracts of land and restoring missing links between them, especially across elevation gradients, creates the “escape routes” plants need to survive climate change. Indeed, statewide modeling of more than 6,000 California plant species shows what’s at stake: by 2080, climate-driven shifts in habitat could cause an average loss of 19% of native species from California’s biodiversity hotspots. Endemic plants, which are those found nowhere else, face even greater risk. Up to 80% of their ranges could vanish within the next century.

Sometimes, we can take more direct action to help plants move. At Pitkin Marsh, for example, we’re working with partners to propagate and relocate rare plants such as white sedge and vine hill manzanita. When a key patch of vine hill manzanita was infected with a deadly water mold, our partners helped move the trees to safe, uninfected ground. And with the Monte Rio Redwoods expansion, we are giving redwoods more room to grow, and thus a better chance to keep reaching for the fog in a changing world.

Movement has always been nature’s way of survival. By protecting interconnected landscapes, we can ensure that plants—and the intricate web of life they sustain—have room to move, adapt, and endure.

Restoring Life to Sonoma’s Waters

The past month has been HOT, and what better activity is there on a hot day than getting out onto the river? Here in Sonoma County, we’re lucky to have the refreshing water of the Russian River to swim or float in. While it may seem only natural that a river should be cool, clear, flowing, and bustling with life on its shores, it’s something we cannot—and must not—take for granted.

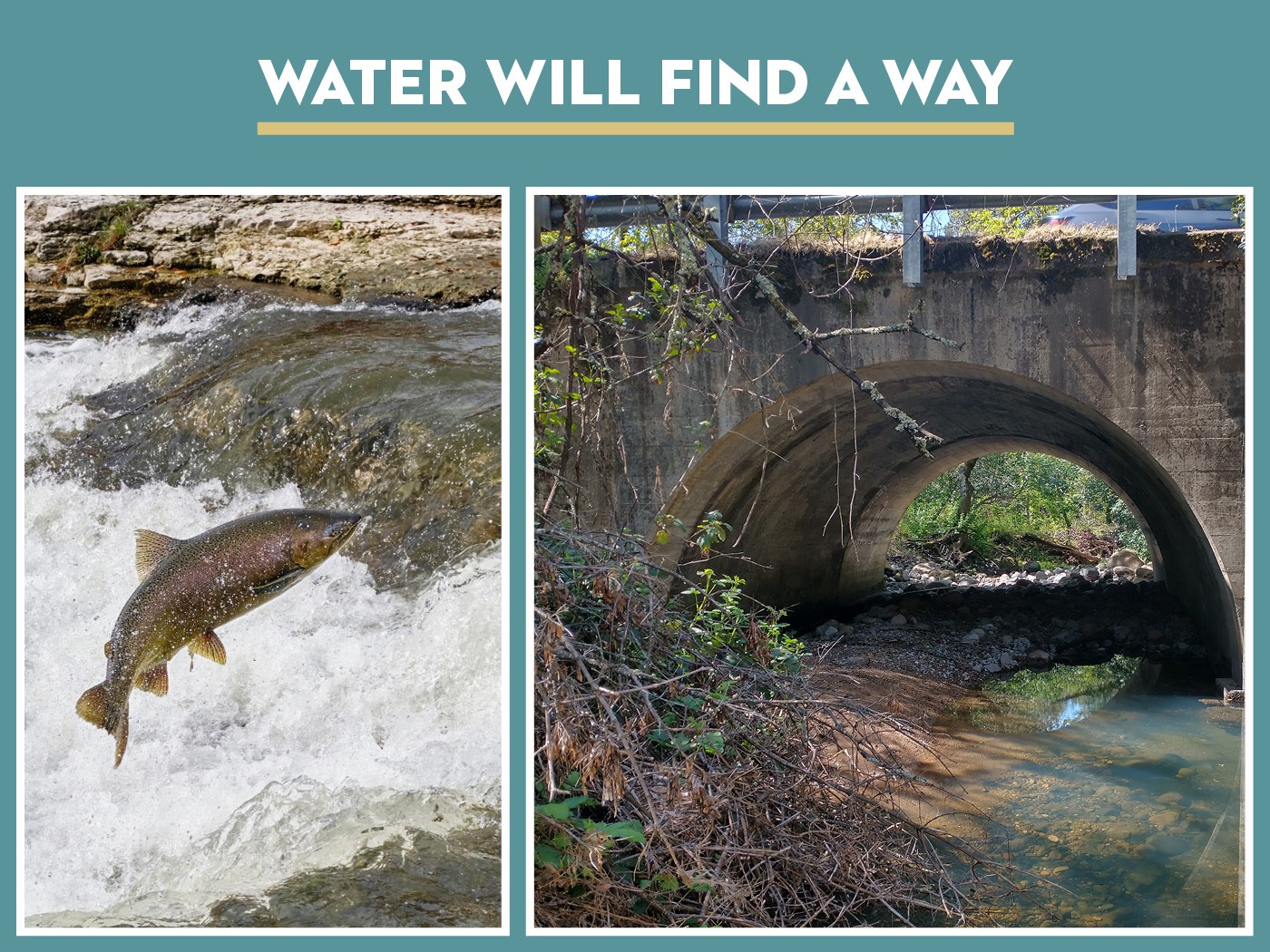

Securing freshwater flows is a cornerstone of Sonoma Land Trust’s strategic plan. Decades of science show that when a creek is channelized or a river diverted, it’s not enough to simply restore a single channel to its former shape; the entire stream valley must be revived so that natural processes can function again, restoring the waterway’s life-giving relationship with the ecosystems it flows through. Across Sonoma County, we’re restoring the natural processes that allow water to move freely again, bringing rivers, creeks, and wetlands back into balance so that water can go where it wants to.

At Lakeville Creek, we’re using a “Stage Zero” approach to revive an entire stream valley. After over a century of heavy grazing and other land uses, Lakeville Creek existed as an eroded ditch-like channel, but we’re transitioning it back to its natural form of a wet meadow with subtle swales of wetland flora. By addressing the deeply eroded ditch-like channel, rain can slowly flow across the floodplain, allowing water to sink into the ground. We’re helping replenish aquifers, support fish and wildlife, and reduce the risk of catastrophic fire. This project is part of our broader Sonoma Creek and Petaluma River Baylands Strategies, which aim to reconnect historic waterways throughout the watershed.

That same philosophy extends north into the Russian River watershed, where we’re working with partners to safeguard streamflow and headwaters that support both wildlife and human communities. Cool tributaries like Dutch Bill and Green Valley creeks act as vital thermal refuges, maintaining the cold, persistent flow coho salmon and steelhead need during dry summers to complete their life cycles. Conserving properties such as Foppiano Ranch—nestled in a horseshoe loop of the river near Healdsburg—ensures over 700 acre-feet of groundwater recharge each year. That’s enough for roughly 3,600 households! It also secures nearly three miles of undeveloped riverfrontage that filters drinking water for more than 600,000 residents in Sonoma and Marin counties, and preserves intact floodplain meadows and woodlands that provide habitat connectivity and reduce erosion. Likewise, the recent Monte Rio Redwoods Expansion protects the headwaters of three key Russian River tributaries—Willow, Dutch Bill, and Freezeout creeks—ensuring clean water for downstream communities while providing the cold, flowing habitat coho salmon and steelhead trout need to thrive.

These projects share a common goal: a Russian River flowing with life, one that continues to deliver clean, reliable water for our aquatic and terrestrial communities alike.

And the results speak for themselves. A decade after we removed obsolete dams at Glen Oaks Ranch and along Stuart Creek Run, reopening more than two miles of spawning habitat for Chinook and steelhead, the salmon returned. After decades of severed connection, they managed to find their way and eventually made their way back up the tributary of Sonoma Creek. All they needed was an open, watery road and sufficient levels to keep them moving.

Even seemingly small interventions make a difference: an upgraded culvert under Arnold Drive now allows both water and wildlife to move more freely through an urbanized landscape.

Water is the most important life-giving force. For fish, plants, wildlife, and people, movement keeps ecosystems alive and in balance. Let’s work together to keep our beloved waters flowing for generations to come.

Celebrated National Parks Leader Brings His Experience to Sonoma

Board Member spotlight

For decades, the Bay Area has nurtured some of the nation’s most influential conservation leaders. Among them is Frank Dean, whose journey began as a geography student inspired by activists fighting to save San Francisco Bay. From ranger to park superintendent to nonprofit leader, Frank has dedicated his life to protecting land and helping people connect with it. Today, he brings that passion and experience to Sonoma Land Trust.

Though Frank had an inclination toward environmental work, he didn’t always know where he fit into the conservation picture. Born in Philadelphia and raised in a military family, he moved often as a child before landing in San Diego for high school. When he came north to attend San Francisco State University, he chose to study geography, a field that investigates how people and the environment shape one another, and the Bay Area was the perfect place to do that. As Frank got to know the shimmering bay and its history, he learned that a lot more of the bay might’ve been filled in and developed had it not been for the efforts of early environmentalists who organized and fought to protect it. “This was where people wanted to do the right thing for the land, not just make a buck,” he recalls. “These were my people.”

A summer job in college as a park ranger solidified his path. Stationed on Alcatraz Island, Frank gave in-person tours, sharing stories of the park’s human history against the backdrop of the Bay. He went on to serve in Sequoia, Grand Canyon, and Yosemite National Parks before returning to Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) and Point Reyes National Seashore. His National Park Service career culminated in serving as the superintendent of GGNRA—the same park where he began. “It was really cool to start and end in the same place,” he says, “because I knew the park well enough to know what I wanted to fix and have the authority to make a difference.”

Over the years, Frank saw former military lands transform into beloved public spaces. One of the most dramatic examples was Crissy Field. When Frank started in the park service, Crissy Field was a decommissioned airstrip on the Presidio waterfront. By the time he returned to GGNRA, the former airstrip had been transformed into a tidal marsh, a beach, and one of the most popular gathering places in the city. He participated with Tunnel Tops Park, a visionary project he helped get off the ground that turned a former inner-city freeway into the nationally award-winning parkland of nature play areas, overlooks, and panoramic views of the Bay.

From the park service, Frank went on to lead the Yosemite Conservancy for a decade, raising millions of dollars for trail restoration, habitat recovery, and landmark acquisitions, including a 400-acre meadow system that is now officially protected as part of Yosemite National Park. Under his leadership, the degraded meadow was restored back to a thriving habitat for a variety of rare plant and animal species, including the rare Yosemite population of great gray owls, and transferred over to the park. He saw firsthand how philanthropy could move quickly where government could not, and it convinced him of the power of nonprofits to drive conservation.

When the pandemic kept him closer to home in Petaluma, Frank began exploring Sonoma County more deeply. “I realized how beautiful it is, and I felt like I wanted to give back, to use what I’d learned in my career to help on local issues,” he says. He started looking at the organizations doing conservation work in the county and quickly found himself drawn to Sonoma Land Trust. It stood out, he recalls, for being both effective and financially stable—big enough to make a difference, yet nimble enough to act quickly. After connecting with longtime colleagues and friends already involved with the Land Trust, he knew it was the place where he could contribute his experience most meaningfully.

Today, Frank serves on our board of directors and is the newly minted chair of the philanthropy committee where he’s helping strengthen our capacity to act when the time is right. “It’s about building our reserves so we can be nimble,” he says. “If a strategically critical property comes up for sale, we want to be ready to move.” He points to projects like the Baylands acquisition and restoration—once a single landscape-scale initiative, now a visionary program reconnecting tidal wetlands and preparing the region for sea level rise. He also points to a new project on the coast that will provide more public access and habitat protection as an example of how the Land Trust brings science, strategy, and partnerships together at the right time to deliver on our bold vision for conservation.

For Frank, the work is also about visibility and inspiration. He hopes more people will recognize Sonoma Land Trust’s role in preserving the landscapes they love and see themselves as part of that effort. “This county is so diverse—ocean, bay, wine country, mountains,” he says. “People all over the country know the name Sonoma. We have a responsibility to keep it special.”

From ranger to superintendent to nonprofit leader, Frank’s career has been focused on protecting land and connecting people to it. Now, with Sonoma Land Trust, he’s helping shape the next chapter; one where conservation is proactive, strategic, and rooted in community. “We’re big enough to make things happen,” he says, “and small enough to stay focused on what matters most.”

News

Welcome Matthew Cadigan, Philanthropy Operations Associate

Born and raised in Sonoma County, Matt brings extensive experience working with nonprofits, managing volunteer programs, maintaining complex databases, and even founding a nonprofit in 2017. He combines nonprofit experience with a strong background in database administration and a passion for mission-driven work. Outside of the office, he can be found biking, kayaking, or diving into the vibrant Bay Area theater and film scene—both performing and directing.

Protecting Sonoma, One Month at a Time

When Sonoma Land Trust acquires land, it’s not a one-time transaction. It is a commitment to stewarding the land to be enjoyed for generations to come. To ensure the ongoing conservation of the land and waterways of Sonoma County, please become a monthly donor with your gift of $10, $25, $50, or even $100 each month.

Why consider giving monthly?

It’s easy! Make your gift now via your credit or debit card or bank account, and your gift will automatically be processed each month, so your support will never lapse. Spreading your support of Sonoma Land Trust throughout the year is a convenient way to fit your donations into your personal budget.

It’s effective! Monthly giving is the most cost-efficient way to support the Land Trust, allowing us to better estimate revenue amounts and timing, which helps us respond to land conservation opportunities when they arise and support the ongoing stewardship of the land. Plus, your monthly gift will automatically renew your membership – reducing the amount of mail you receive from us.

And it’s under your control. You can contact us by email at membership@sonomalandtrust.org or by phone at (707) 526-6930 anytime to cancel or change the amount of your monthly gift . . . we’re always happy to help.

Your generosity will help Sonoma Land Trust combat the effects of climate change, promote the biodiversity of our region, and deepen our connection to the natural world.

You’ll also have the satisfaction of knowing that you are doing your part – all year long – to protect the best of Sonoma County. Plus, if you join as a monthly donor by the end of this month, we’ll send you a limited-edition bandana as a small token of our appreciation.

Please show what Sonoma County means to you each and every month and become a monthly donor today.

SB131 Action Alert

On June 30, the Legislature passed, and the Governor signed SB 131—a sweeping CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act) rollback that threatens wildlife, biodiversity, community health, and opens the door for advanced manufacturing projects to bypass environmental review.

Lawmakers promised to fix SB131 before the end of the session—but time is running out. Unless they act, California’s birds, butterflies, salmon, mountain lions, and countless species could face devastating habitat loss.

Call your State Senator and Assemblymember today: Tell them to keep their word and pass a CEQA clean up bill that protects our communities and ecosystems.

Free Language of the Land Webinars

Language of the Land: Forest Fuels Reduction and Bird Populations

Tuesday, September 16, 7–8:30pm

Join ecologist Ryan DiGaudio of Point Blue Conservation Science and Ryan Berger of The Wildlands Conservancy to learn about a multi-year study of woodland bird populations on four Sonoma Land Trust-protected lands. This study focused on forests where fuel reduction methods were implemented for increased wildfire resilience. Through monitoring bird populations, we gained insight into the links between forest fuels management and overall ecosystem health. Join us to find out the results!

Language of the Land: Ancient Forests of Sonoma County

The remains of ancient trees have been found at several locations in Sonoma County. In this talk, retired State Archaeologist Breck Parkman highlights two of his important discoveries. The first was a Sitka spruce at Bodega Head, remnants of which were exposed during a winter storm. The second was a Monterey pine found eroding from Sonoma Creek. Both trees were many thousands of years old, dating to the last Ice Age. Discover in this talk the nature of the ancient forests of Sonoma County, how they moved, and the significance of finding an ancient Sitka spruce and Monterey pine growing here at the end of the Ice Age. What might that mean in a world facing a changing climate?

Free outings

Join us out in nature this month! Celebrate California Biodiversity Day with a BioBlitz on the Southeast Greenway. Celebrate Latino Conservation Week with a hike in the redwoods. Join us at the Santa Rosa Creek Headwaters with our monthly bilingual Familias al Aire Libre/Families Outdoors. Or hike with us to the top of Pole Mountain!

Many of these outings are in partnership with Sonoma County Ag + Open Space.

Staff recommendation

Anote’s Ark, a feature documentary about the Pacific Island nation of Kiribati, resonated with Bianca Vargas, stewardship technician at Sonoma Land Trust. The film follows former president Anote Tong fighting to preserve his country from rising seas, and a mother, Tiemeri, seeking safety for her children. “Kiribati contributes little to climate change, yet suffers the most, with little support from developed nations,” Bianca says. “I also connected with Tiemeri’s immigration story—it mirrors my mom’s and my own journey to the U.S.”

You can watch Anote’s Ark and find other ANHPI documentaries here.