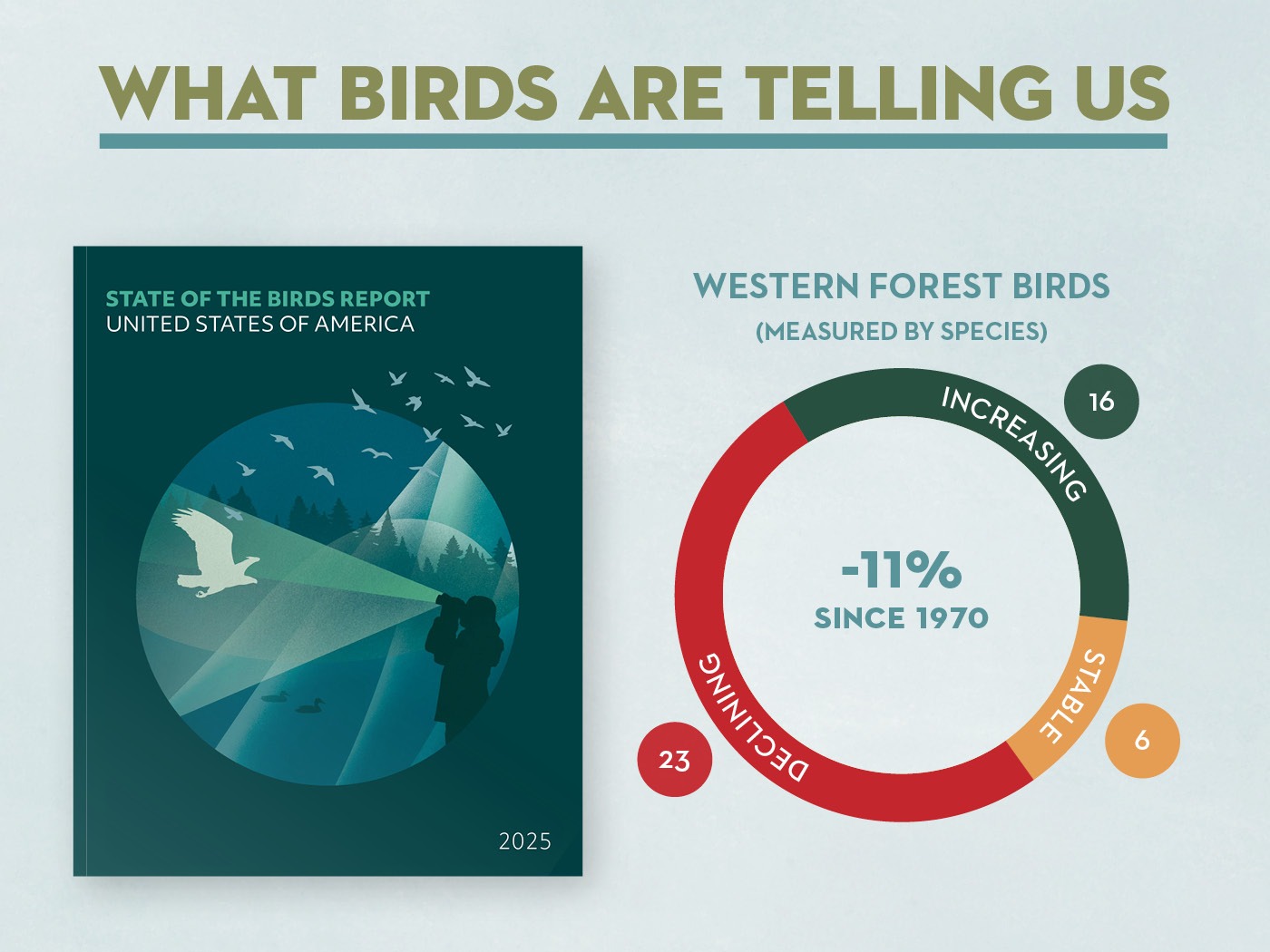

State of the Birds 2025: Alarming Declines

Every year, the State of the Birds report provides a crucial snapshot of America’s bird populations, serving as both a barometer of environmental health and a compass for conservation. This year’s message is loud and urgent: about one-third of all U.S. bird species require immediate conservation action. Birds are sounding the alarm, and we need to listen.

Bird populations are declining across every habitat type, from grasslands to coasts, and from deserts to forests. The 2025 report builds on the devastating 2019 finding that North America has already lost 3 billion birds since 1970. Now, researchers say we’re in a “full-on emergency across all habitats,” according to Marshall Johnson of the National Audubon Society (source).

At the heart of this year’s warning are 112 Tipping Point species, birds that have lost over half their populations in the past 50 years and are projected to lose another 50% in the next 50 without intervention. Among these, 42 species fall into the Red Alert category, with perilously low populations and steep declines. These birds are not just vanishing they are waving red flags about the health of the planet we all share.

What birds are telling us

Like humans, birds suffer from habitat loss, climate change, and environmental degradation. However, unlike us, they serve as immediate indicators of ecosystem distress. The old saying about “a canary in the coal mine” rings truer than ever: when birds disappear, they signal that something is deeply wrong.

In Northern California, particularly in places like Sonoma County, several Tipping Point species are raising concerns. Allen’s Hummingbird (Selasphorus sasin), once common along the coast, has declined sharply due to habitat degradation and shifting climates. Ridgway’s Rail (Rallus obsoletus), another Sonoma-area resident, faces threats from wetland loss and sea-level rise. Both species urgently need conservation action.

Other species native to Northern California that appear on the watch list include:

- Rufous Hummingbird — a long-distance migrant threatened by disappearing food sources and warmer springs.

- Yellow-billed Magpie — endemic to California and vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and disease.

- Tricolored Blackbird — once abundant in California’s Central Valley, now suffering from wetland loss and agricultural changes.

- Marbled Murrelet — reliant on coastal old-growth forests, which are shrinking due to development and logging.

The good news: conservation works

While the trends are grim, there’s also a powerful takeaway from this year’s report: conservation works. Targeted actions have already helped particular waterfowl and waterbird populations rebound. Locally, efforts like those at the Sonoma Creek Baylands show what’s possible. By protecting and restoring critical habitats, organizations like Sonoma Land Trust are offering real help to birds like the Ridgway’s Rail and restoring the broader ecosystems they depend on.

Private land trusts, government agencies, and community groups must continue to invest in bird-friendly policies, habitat restoration, and climate resilience strategies. Science-informed conservation isn’t just a hopeful idea it’s a proven solution!

What we can do together

Birds are telling us something, and it’s time we listen. Supporting local conservation organizations like Sonoma Land Trust is a direct way to take action. By helping to preserve and restore habitats, you can contribute to reversing bird declines and protecting the natural legacy of Northern California.

The 2025 State of the Birds report is more than a data set: it’s a call to action. For the birds, for the ecosystems they anchor, and for ourselves — the time to act is now. Please join us!

Not-so-silent messengers: how birds convey forest health and resilience

Photo: © Olive-sided Flycatcher by Luke Seitz; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Birds have long been recognized as early warning systems for environmental change. Their presence or absence provides critical insight into ecosystem health, biodiversity, and the effectiveness of land management. A recent multi-year bird monitoring initiative across four of our preserves reveals a promising story: thoughtful forest management can reduce wildfire risk while supporting vibrant bird populations.

A decade of bird monitoring sets the stage

In 2013, the Sonoma Land Trust (SLT), Point Blue Conservation Science (Point Blue), and The Wildlands Conservancy (TWC) initiated a monitoring program to understand the impact of forest management on avian diversity across several SLT properties. These early efforts established an unexpected asset—baseline data that would become a goldmine nearly a decade later.

Fast forward to 2022: the team revisited the sites with a more focused question: how are birds responding to shaded fuel breaks and other forest treatments designed to reduce wildfire risk.

Between 2022 and 2024, Point Blue’s Ryan DiGaudio, in coordination with TWC’s Ryan Berger, and SLT’s Shanti Edwards and Melina Hammar, conducted spring bird surveys across four key preserves, including TWC’s Jenner Headlands Preserve, and three SLT properties: Pole Mountain, Little Black Mountain, and Bear Canyon Wildlands. The four sites have been carefully managed using shaded fuel breaks and prescribed fire, offering varied landscapes that support a broader diversity of habitats in Sonoma County. However, all sit within fire-prone zones, where forest health and fire resilience must go hand in hand.

The researchers concentrated on focal species, which are birds that have specific habitat needs (such as old-growth forests or dense shrub understory) and can help measure the success of conservation efforts.

Here’s what they found:

- Jenner Headlands: 65 species detected, including 22 focal species

- Pole Mountain: 27 species, 8 focal species

- Little Black Mountain: 29 species, 13 focal species

- Bear Canyon Wildlands: 39 species, 12 focal species

They also recorded species of special concern, such as the Olive-sided Flycatcher, Vaux’s Swift, and Purple Martin, underscoring the habitat value of these conserved lands. These three species are sensitive to ecosystem changes, making them effective barometers that help researchers assess the impact of various forest management treatments.

Early results are promising

Across all preserves, wildfire resilience treatments had either a neutral or positive effect on the number of bird species and the overall abundance of birds. In some cases, species richness increased compared to baseline surveys from a decade prior.

Even better, the treatments created “edge habitats,” the transitional zones between different forest types that tend to boost species diversity. This suggests that forest thinning and fuel reduction, when done thoughtfully, don’t degrade wildlife value. On the contrary, they can enhance it. For example, for species that nest in the understories of forests, early indications show that certain forest treatments do not decrease their population size. This furthers the question – and possibility – of how we can manage forests in a way that directly supports our long-term conservation goals, reduces wildfire risk, and restores habitat for the benefit of all.

Why this work matters

With the increasing impact of climate change and the risk of future wildfires, we remain committed to active forest management. Studies like these are vital to understanding how conserved lands can serve as wild sanctuaries for birds and as outdoor labs that advance science-based stewardship across the country. The research requires funding and time, and we’re grateful to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology for making this recent study possible.

Land trusts can do a lot for birds, and forest management should be considered as part of that action. Looking ahead, the next phase of this work will include continued monitoring, adaptive stewardship, and sharing findings across a broader network. In Sonoma County and beyond, the main takeaway remains clear: listen to the birds. How many bird species are in a given habitat? What, if any, indicator species live there? Are their populations growing or shrinking?

If we listen, the birds are telling us how conservation works wonders when it is guided by science and grounded in stewardship. We are grateful to our partners at The Wildlands Conservancy and Point Blue Conservation Science for sharing their time and expertise in this critical research.

Mensajeros no tan silenciosos: cómo transmiten las aves la salud y resiliencia del bosque

Hace mucho tiempo que las aves fueron reconocidas como sistemas de advertencia temprana para el cambio climático. Su presencia o ausencia proporciona información crítica acerca de la salud del ecosistema, la biodiversidad y la efectividad de la gestión de las tierras. Una iniciativa reciente de observación de aves durante varios años en cuatro de nuestras reservas revela una historia prometedora: la gestión considerada de los bosques puede reducir el riesgo de incendios forestales mientras respalda las poblaciones de aves llenas de vida.

Una década de observación de las aves prepara el terreno

En 2013, Sonoma Land Trust (SLT), Point Blue Conservation Science (Point Blue) y The Wildlands Conservancy (TWC) iniciaron un programa de observación para comprender el impacto de la gestión forestal sobre la diversidad aviaria en varias propiedades del SLT. Estos esfuerzos tempranos establecieron un activo inesperado: datos de referencia que se convertirían en una mina de oro casi una década más tarde. Pasemos a 2022: el equipo volvió a visitar los sitios con una pregunta más precisa: cómo responden las aves a los cortafuegos con dosel arbóreo y a otros tratamientos forestales diseñados para reducir el riesgo de incendios forestales.

Entre 2022 y 2024, Ryan DiGaudio, de Point Blue, en coordinación con Ryan Berger, de TWC, y Shanti Edwards y Melina Hammar, de SLT, realizaron muestreos de aves en primavera en cuatro reservas clave, entre las cuales se incluyeron la reserva Jenner Headlands Preserve de TWC y tres propiedades de SLT: Pole Mountain, Little Black Mountain y Bear Canyon Wildlands. Los cuatro sitios fueron gestionados cuidadosamente mediante el uso de cortafuegos con dosel arbóreo e incendios controlados, lo que ofrece entornos variados que respaldan una diversidad más amplia de los hábitats en el condado de Sonoma. No obstante, todos se ubican en zonas propensas a incendios, donde la salud del bosque y la resiliencia ante incendios deben ir mano a mano.

Los investigadores se concentraron en especies de interés, que son aves que tienen necesidades de hábitat específicas (como bosques antiguos o sotobosques con arbustos densos) y pueden ayudar a medir el éxito de los esfuerzos de conservación.

Estos fueron los hallazgos:

- Jenner Headlands: 65 especies detectadas, entre las cuales se incluyen 22 especies de interés

- Pole Mountain: 27 especies, entre las cuales se incluyen 8 especies de interés

- Little Black Mountain: 29 especies, entre las cuales se incluyen 13 especies de interés

- Bear Canyon Wildlands: 39 especies, entre las cuales se incluyen 12 especies de interés

También se registraron las especies de interés especial, como el Papamoscas Oliváceo (en inglés, Olive-sided Flycatcher), el Vencejo de Vaux (en inglés, Vaux’s Swift) y el Martin Morado (en inglés, Purple Martin), destacando el valor del hábitat de estas tierras preservadas. Estas tres especies son sensibles a los cambios en el ecosistema, lo que las convierte en barómetros eficaces que nos ayudan a evaluar el impacto de los tratamientos de gestión forestal.

Los resultados iniciales son prometedores

En todas las reservas, los tratamientos de resiliencia contra los incendios forestales tuvieron un efecto neutral o positivo sobre la cantidad de especies de aves y la abundancia general aviaria. En algunos casos, la riqueza de las especies aumentó en comparación con los muestreos de referencia de una década antes.

Mejor aún, los tratamientos crearon “hábitats periféricos”, las zonas de transición entre diferentes tipos de bosques que suelen impulsar la diversidad de las especies. Esto sugiere que el clareo forestal y la reducción del combustible, cuando se realizan de forma deliberada, no degradan el valor de la vida silvestre. Por el contrario, pueden mejorarlo. Por ejemplo, en el caso de las especies que anidan en los sotobosques, las indicaciones tempranas muestran que determinados tratamientos forestales no reducen el tamaño de su población. Esto plantea la pregunta (y la posibilidad) de cómo podemos gestionar los bosques de una manera que respalde directamente nuestros objetivos de conservación a largo plazo, reduzca el riesgo de incendios forestales y restablezca el hábitat para el beneficio de todos.

Por qué es importante este trabajo

Con el impacto creciente del cambio climático y el riesgo de futuros incendios forestales, nos mantenemos comprometidos con la gestión forestal activa. Los estudios como estos son fundamentales para comprender de qué manera las tierras preservadas pueden servir como santuarios de vida silvestre para las aves y como laboratorios al aire libre que hacen progresar la mayordomía basada en la ciencia en todo el condado. La investigación requiere financiación y tiempo, y estamos agradecidos con el Laboratorio de Ornitología de Cornell por haber hecho posible este reciente estudio.

Los fideicomisos de tierras pueden hacer muchas cosas por las aves, y la gestión forestal debería considerarse como parte de esa acción. Vislumbrando el futuro, la próxima etapa de este trabajo incluirá observación continua, mayordomía adaptativa e intercambio de hallazgos con una red más amplia. En el condado de Sonoma y más allá, el aporte principal sigue siendo claro: escuchar a las aves. ¿Cuántas especies de aves hay en un hábitat determinado? ¿Qué especies indicadoras (si las hubiera) viven allí? ¿Sus poblaciones crecen o se reducen?

Si escuchamos, las aves nos dicen cómo hace milagros la preservación cuando está guiada por la ciencia y fundada en la gestión y protección. Estamos agradecidos con nuestros socios de The Wildlands Conservancy y Point Blue Conservation Science por haber compartido su tiempo y experiencia con nosotros en esta investigación fundamental.

Explore eBird: discover birds and contribute to science

Whether you’re a seasoned birder or just starting to notice feathered visitors in your backyard, there’s never been a better time to deepen your bird knowledge and support local conservation while you’re at it. Thanks to cutting-edge tools and sophisticated science platforms, you can identify birds, track your sightings, and even contribute to scientific research right from your phone.

Free resources like Merlin, the intuitive bird ID app, and eBird, the global platform for bird sightings, are empowering nature lovers of all ages. eBird lets you track your sightings, explore hotspots near you, and discover seasonal trends in bird activity. Over 1.9 billion observations have already been submitted by birders worldwide, creating one of the most valuable wildlife databases in existence. This data powers conservation decisions, helps land trusts secure grants, and supports participatory science that protects birds and their habitats. Want to learn even more? The Bird Academy from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology offers self-paced courses for every skill level—from the basics of birdwatching to interpreting complex migration patterns.

These tools don’t just boost your enjoyment of birding—they also make a real impact. In Sonoma County, conservation groups use bird data from these tools to monitor forest health, guide land management decisions, and enhance wildfire resilience. Your sightings could help inform the next major conservation effort!

Get involved today

Start by visiting birdtrust.org to access free birding tools, educational resources, and local conservation opportunities. Then, head out to a Sonoma County hotspot like Jenner Headlands or Little Black Mountain, with Merlin and eBird in hand, and discover what birds can teach you about the land we call home.

More birding projects and resources from Cornell Lab of Ornithology:

- All About Birds – Online guide to birds and birdwatching

- Bird Academy – Birding courses and tutorials

- Birds of the World – Life histories for all bird species

- Celebrate Urban Birds – Bilingual, equity-based community science

- Great Backyard Bird Count – Four days of bird counting, each February

- Macaulay Library – Scientific archive of birds and more

- Merlin Bird ID – An app that helps with bird ID

- NestWatch – Database for nest monitoring

- Project FeederWatch – Survey of birds visiting backyards, nature centers, etc.

Not sure where to start? Explore the eBird website or download the app to begin. For beginning birdwatchers, consider trying the self-paced Joy of Birdwatching Course.

Songbirds and white wines go together

Kent and Carol’s Rock and Clay label is a testament to a simple but powerful idea: farming doesn’t have to fight nature—it can work with it. Blending a love of science, a deep reverence for nature, and a passion for winemaking, their story is grounded in a commitment to sustainable agriculture and an appreciation for the wildness that can thrive in vineyards managed with care.

Kent and Carol’s deep love for nature began long before their winemaking days. Hiking has been a source of peace, clarity, and renewal for them for many years; it’s also what brought them to Sonoma Land Trust in the first place and inspires their ongoing support of our work.

Kent’s path to wine began early, paired with his passion for science. At UC Davis, he studied enology, a discipline deeply rooted in chemistry and microbiology. Although he ultimately built a successful career in biotechnology, he continued to fuel his passion for wine with hobby vineyard and garage-scale winemaking projects. It was wine that brought Kent and Carol together. She owned a wine shop in Seattle, where they first met. The rest, as they say, is history.

Carol, who studied psychology, found herself drawn to the wine community for its people and convivial energy. Together, they purchased a small vineyard in Carneros, Sonoma, and began to blend their personal and professional passions of science, nature, and delicious wine. Their original vineyard sat on Meadowlark Lane, aptly named for the flocks of Western Meadowlarks (Sturnella neglecta) that sang from the fence posts each spring. The birds, with their cheerful fluting calls, became the symbol of the land’s vitality and an inspiration for the wine label.

They initially hoped to name their wine “Sonoma Meadowlark” but for licensing reasons decided on Rock and Clay.

“Rock and Clay is a reference to the soil,” Kent says. “You can see how vine growth varies within and between vineyards based on soil characteristics. Soil is the foundation of a terroir and the wine it produces.”

Kent and Carol took a natural approach to vineyard management, transformed their four-acre Carneros plot into a vibrant ecosystem. Instead of using synthetic chemicals and herbicides like Roundup, they opted for compost, gypsum (to break up clay soils and displace harmful salts), and natural predators to control pests. The results were immediate and dramatic.

“We stopped using Roundup and had an explosion of ladybugs that wiped out the scale insects,” Kent says. They also installed owl boxes to attract barn owls, a fierce predator of gophers, which can wreak havoc on vineyard roots. One owl family can consume up to 2,000 rodents a year.

Bluebird and tree swallow boxes added another layer of ecological harmony. “They’re wild animals,” Kent says, “but they love the vineyard—lots of bugs to eat and safe spots to nest.”

This integration of wildlife into farming is rare but meaningful. “Birds are wild animals that actually provide a service to a vineyard,” Kent reflects. “It’s a symbiotic relationship between wild animals and farmers.”

Kent’s scientific training has a profound influence on his philosophy. He views soil as a complex substrate shaped by thousands, even millions of years of geological history. In the Meadowlark vineyard, heavy Haire clay soils retained water and salt, stressing the vines. Gypsum helps displace salts and open the soil structure, improving soil chemistry and drainage.

He’s also attuned to the broader environmental concerns of farming in California, particularly water use. “Most people don’t look at water the way a geologist does,” he says. “If you’re drawing from a 500-foot well, that water may have taken 10,000 years to percolate into the aquifer.” He advocates for less irrigation and better practices like dry farming, as was common in California’s earlier winegrowing days.

Although Kent and Carol no longer farm their own vineyard, they carefully source grapes for production of wine under the Rock and Clay label. Each bottle features a Northern California bird illustration by Roger Hall, often a bird associated with vineyard life.

From the owl on their Sauvignon Blanc to the raven on their Malbec-Tannat blend, each bird evokes both a sense of place and their philosophy: wine is not just about grapes, but about the land, the air, the wildlife, and how all of it is stewarded.

We are deeply honored and grateful for Kent and Carol’s generous support of our work to safeguard Sonoma’s natural and working lands.

You can taste their delicious Rock & Clay Wines at Passaggio & Company in Glen Ellen, Thursday through Sunday from 11 am to 5 pm, with live music most Saturdays, or reach out to them directly online at www.rockandclaywines.com.

Free Language of the Land Webinars

Bay Area Wildlife with Jeff Miller

June 25, 7pm

Join Sonoma Land Trust for a presentation by conservationist Jeff Miller, author of Bay Area Wildlife: An Irreverent Guide. Miller’s talk will cast a spotlight on some of the region’s most charismatic fauna, amazing animal congregations, and mass migrations.

Bringing the Salmon Home with Toz Soto

Background Photo: © Klamath River Copco No. 2 by Swiftwater Films

Learn from Toz Soto, Fisheries Biologist for the Karuk Tribe, about the undamming of the Klamath and its effect on the salmon and water quality. He also covers the fight to remove the dam, as well as the mechanics of the dam removal.

News

Take Action

Join us and the Power in Nature coalition as we stand together to protect our shared natural resources and public lands.

Free outings

This month, experience sound healing and yoga, or join us for The Nature Around Us: Journaling the Santa Rosa Creek Watershed series of summer outings beginning June 18 with an intro to nature journaling workshop by Sarah Reid.

Many of these hikes are in partnership with Sonoma County Ag + Open Space.

Staff recommendation

Sonoma County Feminist Bird Club (Sonoma County FBC) is a friendly group of bird nerds, committed to creating a safe and welcoming space for everyone, regardless of their identities, to learn about birds and their environments. Our mission is to build community around a shared interest in birds, nature, and environmental and social justice.

Birding for a Better World blends the joy of birdwatching with a focus on inclusivity and justice, challenging traditional norms and showing how birding can drive both conservation and social change.