Russian River Subwatershed Conservation Strategy

Coho Salmon Lifecycle

On a spring day in 2016, a one-year-old Coho salmon smolt, having been born and raised in Dutch Bill Creek, which feeds into the Russian River, felt the ancient urge to start its quest down the stream to the river and then to the sea. A passage as old as time. But this particular spring, like the two that preceded it, the creek had dried out before reaching the river due to the drought and the young Coho was unable to move forward. Like many of the thousands of other smolts in that same creek who had begun life with such promise, it did not survive.

The degradation of habitat and lack of sufficient freshwater flows in the river and its creeks, the result of human activities like mining, logging, agriculture, residential development and now climate change, are major reasons that Coho salmon are endangered. The Coho require adequate cool water at every step of their lifecycle: over the summer when they’re growing up, in the spring when they head for the ocean to mature and two years later when they return to spawn.

Where Water is Needed

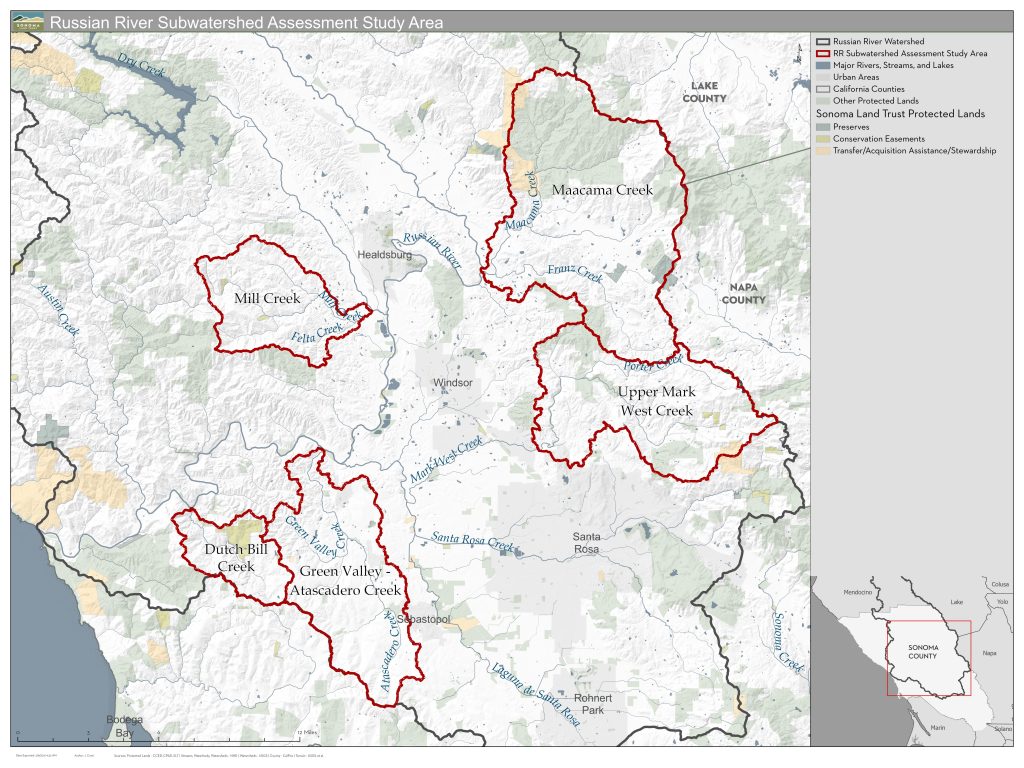

Not surprisingly, what’s good for the fish is also good for the more than 600,000 people who rely on the Russian River for their drinking water. For these reasons, Sonoma Land Trust has developed a new strategy based on the latest science for targeting areas in five tributaries of the Russian River Watershed where the need for streamflow is greatest for Coho — and where there are partners already working with whom we can collaborate. We are focusing on the Dutch Bill Creek, Green Valley Creek, Maacama Creek, Mark West Creek and Mill Creek watersheds.

Connection Between Land and Water

Water flows across the land from rain and then either flows underground to creeks or is held in underground aquifers — natural storage areas carved out of rock that hold groundwater. Groundwater supports flows in the river, especially through the drier months when there is little rainfall. The flow of groundwater into rivers as seepage is essential to the health of the wild animals and plants that live in the water.

The land filters the water (through healthy soil and plant roots) before it reaches the river, but it can also convey pollutants from developed land, like pesticides, automobile oil, etc. Therefore, the quality of the water in your well, tap or creek is influenced by what is happening on the land.

Where We Work

Sonoma Land Trust is using the latest science and new technology to determine the land areas in the creeks’ watersheds that are most essential to the survival of Coho salmon. We’ve asked the questions:

- With over 10,000 properties in the five watersheds, where does it make the most sense to invest resources?

- How can the Land Trust best complement the work of others who are helping to keep Coho in the Russian River Watershed?

Starting with the places where there is good habitat for fish, we’ve developed a Conservation Value Metric that combines data representing three different aspects of the ecosystem that are important for salmon:

- Upland and Riparian Habitat

- Instream Habitat

- Streamflow

This metric identified high-priority areas where we can match the most relevant conservation action.

With such strategic data, Sonoma Land Trust is able to do much more targeted outreach to the right landowners and make a bigger and faster impact.

Both Traditional and New Tools

The Land Trust considered how it could use its unique skills to make a meaningful difference to improve streamflows in the five subwatersheds. In addition to our traditional tools of buying and managing land and using conservation easements to protect land, we determined we could use some innovative approaches, like water transactions, to ensure there is water in key locations at times of critical need for Coho.

A water transaction could be an agreement with a willing landowner to reduce water use during critical dry periods or installing a storage tank to fill during the winter for use in the summer — instead of taking water from a creek or spring when the fish need it most.

Bringing the land connection to the work other organizations are doing to ensure more water in the streams might make the crucial difference the next time a Coho heads for the ocean.